Summary

The first electoral round was won by former President Lula. However, the incumbent, Bolsonaro, performed better than expected. Their economic agendas differ on a number of issues, while risks are more asymmetric under each candidate. Either could benefit from a robust macroeconomic scenario.

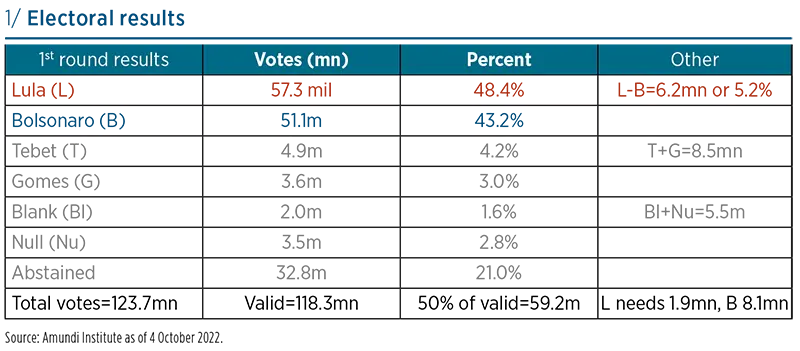

The first round of Presidential election took place on 2 October. As expected by great majority of polls, the Workers’ Party’s candidate and former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva led after the first round and came close to winning the election outright, as predicted by several polls. However, traditional pollsters were wrong when it came to the result of incumbent president Jair Bolsonaro, who outperformed and narrowed the gap to Lula to a mere 5 percentage points(pp) (48% to 43%), while the spread projected by polls was almost double on average.

Third-wave candidates, and Ciro Gomes in particular, disappointed. Turnout proved to be in line with the 2018 election and the rate of absenteeism was 21%.

The Congressional election took place on the same day. All seats in the lower house, one-third of the Senate seats, and 27 state governorships and state legislators were up for re-election. The Congressional election delivered a strong showing for right-leaning parties and the President’s Liberal Party (PL). In fact, Bolsonarismo did even better than the President himself.

Based on the Brazil’s recent history, Lula has an edge heading into the second round, as he won the first round. Over the past six presidential elections, first-round winners have also won the second round. The former president is comfortably ahead in the polls, even though those polls must be taken with a pinch of salt at this time, and is much closer to the hypothetical finish line of 59.2mn votes than Bolsonaro (see table).

We are constructive about the first round results for a variety of reasons. Firstly, Lula’s mandate for leftist policies decreased with the closer-than-expected first-round results, while his views will have to moderate further if he wants to attract centrist voters. Secondly, the centrist/centre-right Congress -- an important arbiter in today’s Brazilian political system – will be a further constraint on Lula’s potentially populist ideas. Finally, while having to come back from behind, Bolsonaro has the momentum and some tailwind from the three largest states, keeping the pressure on Lula’s centrist message. On the other hand, the tighter the race is, the bumpier the potential transition of power could become. The second round will take place on 30 October.

The first round was won by Lula; however Bolsonaro performed better than expected

Strong economic background

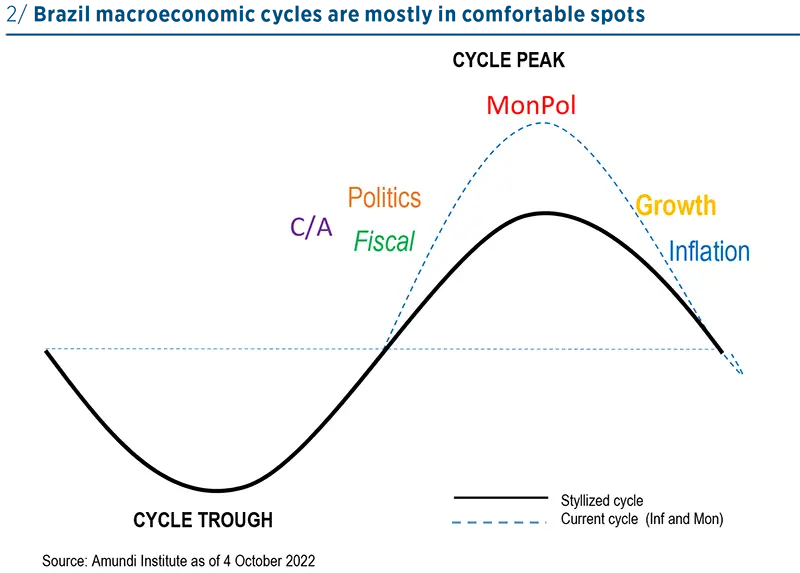

Whichever candidate wins in late October will be met by a strong cyclical outlook but weaker structural trends. Brazil’s growth appears to be peaking after a robust performance so far this year, driven by the reopening of the services sector, elevated terms of trade (ToT), strong credit and employment cycles, and a large fiscal stimulus, worth some 1.5% of GDP. Economic activity is not expected to falter, even though it will be affected by tight monetary policy and softer credit cycles, due to Brazilian households’ being highly leveraged. We expect a soft landing thanks to a strong agricultural sector output, moderating inflation, and still decent labour market dynamics that have benefited from the 2017 labour market reform. Fiscal momentum is unlikely to turn negative under either administration. We project annual real GDP to expand by around 3% this year and by more than 1% in 2023, with a large part accounted for by carryover. 2023 growth will depend much on the state of global economy and on the future administration’s action.

On the inflation front, Brazil is leading the global inflation cycle. Headline inflation peaked in April at 12.1% YoY and will be less than half by year-end, due to federal and state tax cuts and energy price declines. Core inflation has also peaked, thanks to core goods disinflation, while services inflation has yet to start moving lower. While dropping to around the upper end of the inflation target range is relatively easy – also thanks to favourable base effects – moving to the middle of range (3.25%) will take more time, effort, and even luck. We expect inflation to hit these levels only in 2024.

Monetary and fiscal policy outlook

On the monetary policy front, the Central Bank of Brazil (BCB) is the first EM central bank to be done with rate hikes. While the US Federal Reserve (Fed) has been front-loading hikes trying to deflate the economy and the labour market, the BCB looks done now after a hiking cycle that lasted one and a half years and resulted in the policy rate being raised by nearly 12pp (to 13.75%). The tightening cycle ended in September via the first split decision (7-2) since 2016, while the statement was hawkish. In fact, the BCB made it sound like a pause, by stating that it would “not hesitate to resume the tightening cycle” if necessary and otherwise employ a wait-and-see strategy “for sufficiently long.” Given the softening growth outlook, moderating inflation, and the passively tightening real monetary policy stance (via slowing inflation), we see the BCB kicking off the easing cycle already in Q1 2023, with ex-ante real rates around 8-9%, while the Fed is likely to be still hiking rates by then.

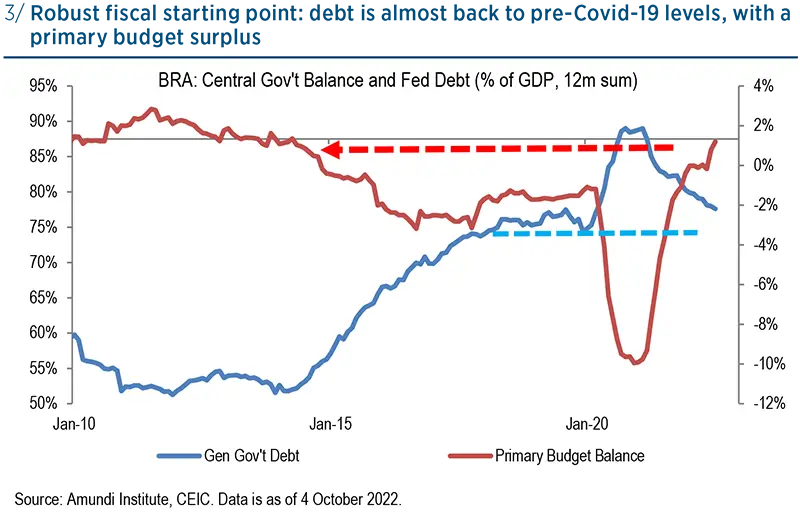

We see mild twin deficits building up. Brazil’s primary budget is running in surplus for the first time in several years despite large pre-election fiscal stimulus and tax cuts, thanks to robust GDP growth, strong ToT, and high inflation (the structural primary deficit is around zero). At the same time, the current account deficit is more than fully covered by FDI inflows. In addition, the public debt-to-GDP ratio has improved much from the Covid-19 crisis peak of around 90%, falling back to around pre-Covid-19 levels (77%).

To sum up, the starting fiscal point looks benign in relative terms for any incoming administration.

However, the cyclical outperformance won’t last forever with structural deterioration – though not a radical one – eventually taking over, regardless of who takes office on 1 January. This is because both presidential candidates are advocating changes to the country’s ultimate fiscal anchor, the spending cap, which fixes government spending in real terms, driving it lower as a share of GDP. Lula would want to eliminate it altogether, while Bolsonaro would make it a function of nominal GDP growth. This would allow both candidates to keep Auxilio Brasil transfer payments at the temporarily boosted level of BRL 600 per month, worth over BRL 50bn, or 0.5% of GDP in extra expenditure. This is likely to be prioritised and handled via a waiver. Lula would also spend more on public capex, increase minimum and public servant wages.

A big chunk of money would also need to go towards paying off ‘precatorios’ and reimbursing states for tax cuts introduced recently. All in all, spending as a share of GDP is likely to head higher to over 19.0% of GDP from the budgeted 17.6% in 2023. At the same time, the primary surplus is likely to drop from the forecasted 0.6% of GDP back into deficit. Such spending trajectory would worsen the debt-to-GDP ratio, unless offset by corresponding increase in revenues, and raise it to mid-80s percentages over the coming years, especially if Lula wins.

BCB is the first EM central bank to be done with rate hikes

Election and financial markets

On the financial markets, there is little concern about the election result and the impact of fiscal accounts. However, Lula has potentially less orthodox ideas to implement, in line with his preference for state intervention. These include unwinding the 2017 labour market reform that introduced new outsourcing regulations and more flexible hiring scheme for temporary workers, even if Lula has refrained from talking about this idea recently.

Another idea is increased activity by the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), which misallocated capital and deemed monetary policy far less effective via the subsidised lending rate in the past, even though BNDES recapitalisation would certainly be much lower now and fiscal guarantees used more widely instead. Lula’s overall stance on stateowned enterprises (SOEs) could also weaken their governance and the lack of appetite for privatisation is evident. On the spending side, there is the already mentioned spending cap elimination to allow increased outlays on a number of initiatives and dislike for the current Petrobras’ fuel pricing policy.

While Bolsonaro would also adjust the spending cap higher, his administration is unlikely to unwind any of the passed initiatives, continuing instead its drive to reform, privatise, and offer concessions of public sector activities. Both Lula and Bolsonaro would try to pass tax and administrative reforms, much to the markets’ appreciation.

Lula’s tax proposal would certainly be more progressive, while also emphasising closing loopholes and cutting subsidies. Both would also want to harmonise state and federal VAT taxes. On the administrative reform front, overall payroll costs could be reduced via changes in hiring regulations of new entrants.

Overall, Bolsonaro’s and Lula’s agendas and their bottom lines do not differ much, but the latter’s presidency would seem to carry more fiscal risks if all his ideas were to materialise and add up and if offsetting proposals got watered down.

Bolsonaro’s and Lula’s agenda do not differ much, but the latter could carry more fiscal risks

Investment implications

The first-round result was positive, with a much narrower gap between Lula and Bolsonaro than markets anticipated. Bolsonaro’s allies in the Senate and in state elections did much better than expected and increased the number of Congress seats.

While the central scenario remains a victory for Lula on 30 October, most likely he will have to move further to the centre, and some of his more extreme policies might be more difficult to pass in Congress. As such, we are constructive on Brazilian assets, especially in the FX and local-currency bonds.

Once the election risk is behind us, we believe that Brazil fixed income should perform well, due to a variety of factors, including:

- Relatively high carry on BRL and rates;

- Positive real rates, which is not the case for most other EMs;

- Brazil is probably the only EM country where we are seeing a peak in rates and in inflation;

- Inflation is expected to be in single digits in 2022 and converge to the CB target by 2023-24;

- CB has stopped hiking rates; and

- GDP growth has been unexpectedly robust in 2022 thus far.

Overall, prospects are brighter for BRL and rates, even though the market is pricing in around 300bp of rate cuts by end-2023. BRL has been one of the best performing EM FXs this year, but with a high carry – currently at 13.75% – it is still worth investing in. It could appreciate further, towards 5 against the USD, or even lower.

In hard-currency bonds, Brazil CDS around 300bp is probably at fair value. We see some opportunities in corporates.

On equities, we expect the Brazilian equity market to rise under any final election outcome, due to various factors. Firstly, we believe the fiscal situation – a key element of Brazil’s financial stability – to be neither good nor catastrophic under either outcome. If Lula wins, he will probably not get enough support in Congress to pass all the social spending he wants to. Secondly, Brazil’s CB began its tightening cycle one year before the Fed’s and should be among the very first countries around the world to ease its monetary policy. This should help growth to resume. Valuations are also extremely cheap. Brazil is insulated from geopolitical turmoil, is self-sufficient energy-wise, and should benefit in the long run from its agro-power status.

However, Brazilian equities will probably rise more if Bolsonaro wins, as state-owned enterprises and banks would fare better. This is testified by Lula’s statements. For instance, Lula’s announced that he wants fuels produced by Petrobras to be sold at ‘cost plus’, instead of at international prices. At the sector level, we favour consumer discretionaries and corporates levered to declining long-term interest rates, such as infrastructure and real estate.