LatAm’s dramatic elections calendar that landed three leftist presidents in the Andean region might be two-thirds over, but the political and policy uncertainty created by these election results is far from it. Chile and Colombia are expanding the size and role of the state, while intense political and macro conditions have forced yet another and a big-time government reshuffle in Peru and Argentina, respectively. In Brazil, which has yet to hold elections, Lula leads Bolsonaro comfortably, but the gap has been narrowing there as well.

It has been an eventful, if not dramatic, political cycle in Latin America, driven by anti-establishment sentiment and public discontent with the status quo, magnified by the economic and health flaws exposed by the Covid-19 crisis. The cycle kicked off a little over a year ago, when Peru elected a (hard) leftist president, followed six months later by a similar outcome in Chile. Then Colombia, and only recently, made it three for three in the Andean region when it comes to left-wing heads of state. This was an even more surprising result there given the country’s political history – it had never elected a leftist president before. But there were also a couple of (mid-term) election results that defied the general trend. Both in Argentina and Mexico, ruling coalitions lost important seats that meant relinquishing a simple majority in the case of Peronists and a qualified majority for Andrés Manuel Lopez Obrador’s party Morena.

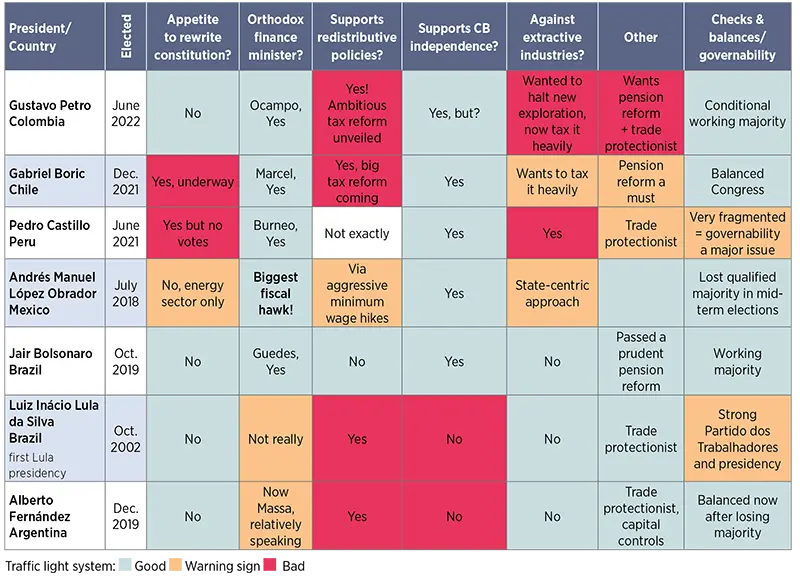

While the election season is two-thirds, the political and policy uncertainty results is far from over. In Argentina, a government reshuffle in a more orthodox direction was needed to arrest a run on the peso and a disorderly economic adjustment that would have undermined further the Peronists’ chance in next year’s elections. In Peru, another reshuffle – there has been on average one ministerial change every several days – was needed to address deep and chronic governability issues under president Pedro Castillo and impeachment is the most likely outcome. Chile’s focus shifted to the constitutional process that will decide if the newly drafted constitution will be implemented or the process restarted. In addition, Gabriel Boric’s administration is advancing an ambitious tax reform and will unveil soon its proposal for a pension reform with significant implications on the economy and society. In Colombia, the electoral transition has been smooth, though the far-reaching tax reform suggests that the administration is full of ambitious proposals in line with the campaign promises.

Brazil will hold elections in October. Former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva leads the incumbent Jair Bolsonaro comfortably, though the polls are showing narrowing dynamics, aided by slowing inflation and boosted by direct transfers. Changes to macro policy are on their way, though they will pale in comparison to the rest of the region, with the exception of Mexico, a relative oasis of political peace in LatAm. Where domestic politics is less of a headwind, frictions on the USMCA free-trade agreement front are worth keeping an eye on as they could undermine otherwise big-time tailwinds, courtesy of the recent geopolitical shocks.

LatAm’s dramatic elections calendar landed three leftist presidents in the Andean region

Below we discuss in more detail country-specific developments of political and policy nature

Colombia: Gustavo Petro’s third time is a charm. A smooth electoral transition and meaningful macroeconomic changes are under way

In June, Petro won the second round of presidential elections against Rodolfo Hernández (a right-wing independent) 50-47%, becoming Colombia’s first ever leftist head of state. The third time was a charm – Gustavo had already run in 2010 and reached the run-off in 2018 – and he became the Andean’s region third left-wing president in this election cycle.

Petro ran on a ambitious leftist platform that included a tax, pension, land and healthcare reforms as well as a ban on new oil exploration The latter could be problematic for a country running sizeable twin deficits. He seemed to have moderated his views between the two rounds, named an orthodox finance minister (José Antonio Ocampo), as Boric did in Chile, and formed (a conditional) working majority in Congress that should avoid Peru-like governability pitfalls. While showing signs of moderation, the recently unveiled tax reform highlighted what the new administration is about – a bigger role for the state, heavier spending via taxation of the rich, corporates and extractive industries, the latter to lean on its size as well – with the ultimate goal of reducing the country’s economic inequality.

We have yet to hear how the additional revenues will be spent, but we suspect a much larger portion will be redistributed rather than saved. While oil windfalls and an overheated economy have stabilised cyclical debt dynamics, Colombia needs a structural plan and a working fiscal rule to keep public liabilities on a sustainable trajectory.

Chile: the rejection win in the constitutional exit referendum will restart the process in a more constructive environment

The newly drafted constitution was rejected in September 4 exit referendum in an ambiguous way - 62% to 38% in favour of reject. The process will continue however given majority sees the old Pinochet-era law of the land as outdated and to prevent a new round of social unrest resembling the events of late 2019.

President Boric is in favour of redrafting Chile’s Magna Carta from scratch (with a more representative constitutional assembly), while the opposition would like to do that via amendments with Congress, already lowering the constitutional majorities needed to pass potential amendments. Whichever path is taken, the next constitution is likely to be of better quality than the one just drafted. That suggests the peak in uncertainty, when it comes to tail risks, is already here though uncertainty will linger for longer.

The government is also working on an ambitious tax reform to raise an additional 4% of GDP in revenues, much of which would be spent on various social programmes. There is also a pension reform to be unveiled that will put further pressure on public coffers. All in all, while under the pragmatic stewardship of finance minister Mario Marcel, the economy is undergoing significant shifts as the size of the state grows and its role changes from a regulator to a provider of services.

The newly drafted constitution was rejected by a great majority of Chileans even tough an even greater portion of the society sees the old Pinochet-era Magna Carta as outdated

Peru: another government reshuffle will not improve governability sustainably and only delays an eventual impeachment

Pedro Castillo’s government sees on average a fresh ministerial nomination every several days – there have been nearly 70 reappointments since the new administration took over in summer 2021. The latest reshuffle a few weeks ago included six ministries, though the prime minister’s resignation was not accepted by the president. The important finance and economy portfolio was handed to Kurt Burneo, a former minister, central bank board member and a politician with more political clout than his predecessor. The other appointments were more questionable and included people previously relieved of their duties, e.g., Chavez. Both the rejection of Anibal Torres’ resignation and subpar appointments to other posts suggest Castillo struggled to recruit ‘serious’ individuals to join his cabinet.

The reshuffle will protract the current suboptimal status quo, where governability is a big issue. Unlike in Colombia, or especially Chile, big time structural/regime changes are less likely, given the lack of consensus on just about anything (including impeaching the current president). Lack of governability is a cyclical headwind, but less of a structural impediment requiring significant market repricing.

The current situation seems unsustainable and will end, we suspect, in an impeachment, also because the sitting president does not want to resign as that would further expose him legally. The opposition is rumoured to be just several votes short of the necessary 87 to get rid of Castillo and is reluctant to pull the trigger on a move that would cost the current congressmen their jobs. An impeachment in Peru also leads to a dissolution of Congress and fresh elections, in which current congressmen cannot participate. As the present erratic situation is unsustainable, we suspect an impeachment will eventually take place.

While new elections would raise political uncertainty in the short term, they are likely to be a step in the right direction, towards a more orderly functioning political ecosystem that would serve the country more constructively in the medium term.

Argentina: a necessary reshuffle to arrest the run on the peso. Addressing the underlying problems is a likely post-election story

The unravelling FX situation in the aftermath of finance minister Martin Guzman’s resignation eventually led to a political reshuffle in August and the appointment of Sergio Massa as a ‘super minister’. He will head the ministry of the economy, production, and agriculture and be in charge of talking to the IMF. Massa, a former chief of staff, presidential candidate, and until recently, the lower house speaker, is considered to be one of the most market-friendly politicians within the ruling coalition and one with a significant political clout. In line with the latter, Massa named a well-trained economist Gabriel Rubinstein as his number two, who is also known for being a fierce critique of the vice president and her policies. This suggests Massa has been given the freedom to implement policies needed to stabilise the economy though at a minimal political cost.

The unbalanced economy desperately needs an orthodox policy response. Massa’s appointment is a much-needed confidence boost that should lead to an improvement in governability and to a reduction in political uncertainty. He will focus on reaching the IMF deal targets, such as closing the primary budget deficit around 2.5% of GDP, reducing monetary financing and tightening monetary policy, e.g., bringing real rates into positive territory – the central bank has been hiking rates aggressively, though hi-flationary price dynamics have nullified much of its progress. When it comes to fiscal adjustment, Massa will hike public utility tariffs and cut energy subsidies in a segmented way, especially to high earners, while tariffs for the low-income population will remain unchanged, and will introduce consumption caps. In addition, public capex and transfers to provinces will be cut, though social assistance programmes will probably rise, not fall.

While Massa’s actions are likely to stabilise the macroeconomic tailspin and the near-term IMF review(s) are likely to pass, in light of next year’s elections, the administration is unlikely to go for what is needed to resolve the underlying economic imbalances, e.g., currency devaluation. In fact, spending and populist pressures are likely to grow as the elections near, implying, in turn, that the macroeconomic starting points will deteriorate by the time the next administration is in place to tackle them.

The unbalanced economy of Argentina desperately needs an orthodox policy response

Brazil: it is election time, but risks seem less pronounced than in the rest of South America

The presidential race is fully on with the first round of general elections scheduled for 2 October. Former president Lula is leading the incumbent Bolsonaro by a comfortable 10% (45% to 35% when averaging across the polls, which diverge widely), though the lead has been narrowing. We suspect the gap will close further, helped by media campaigns, debates, slowing inflation (now back in high single digits), fuel price cuts, and boosted direct transfers (e.g., Auxillio Brasil payments were raised to $R600/month).

While the race is tightening, the markets seem relaxed, though not indifferent, to the two most likely outcomes. On the one hand, the leftist Lula is talking the prudent populist talk and already with a centrist vice president name on his presidential ticket. On the other, the current economy minister Paulo Guedes confirmed he would stay on, were Bolsonaro to win the re-election. Finally, a likely centrist Congress is expected to play a moderating role when it comes to policy actions.

Changes are coming regardless of who is in charge on 1 January 2023. Both candidates want to adjust the spending cap – the country’s ultimate fiscal anchor – and make permanent the recently passed measures of a temporary nature and reshape the tax system, though in a different shape and form. On a more positive note, they also see the need to pass structural reforms such as an administrative reform. All these will have an impact on potential growth, short- and long-term revenues, spending and fiscal paths and, in turn, on inflation expectations and asset prices.

Both candidates want to adjust the spending cap and make permanent the recently passed measures of a temporary nature and reshape the tax system, though in a different shape and form

Mexico: relatively benign domestic politics overshadowed by USMCA frictions

Since losing the qualified majority in 2021 mid-term elections, the Morena coalition has attempted unsuccessfully to pass a constitutional amendment to reform the country’s electricity sector that favoured the state over private participants. In a related issue, nor did the Supreme Court rule in favour of the government initiative, though it did not strike down the proposal altogether. It seems it will be the actions of the international actors, not the domestic ones that pose a hurdle for the AMLO administration within the energy space. USMCA trading partners have launched an official dispute over violation of the trade treaty that will soon progress to a much formal and long-lasting stage of panel negotiations. While the state-centric energy sector is AMLO’s priority, we suspect USMCA is no less important to him for economic reasons. We expect some sort of middle-ground solution will be reached under which a more ‘flexible’ projects and permits-award system will be in place, while the key elements of AMLO’s underlying policies will not change. That would alleviate the risks of a USMCA break up and give the country a strong platform to benefit from meaningful nearshoring trends in light of recent geopolitical events.