Summary

- Election outcome and political scenario: The centre-right coalition won Italy’s general election on 25 September, with approximately 44% of votes. Overall, we believe that Italy’s general election offered no major surprises and at the margin, the news flow is positive, as the centre-right collation will not have a two-thirds parliamentary majority, which would have allowed it to vote for constitutional amendments. At the same time, it has enough seats to form a stable government. Italy could have a new government in early November at the earliest, with the new prime minister likely to be Brothers of Italy’s leader Giorgia Meloni. However, the Brothers of Italy will need its allies to ensure a solid parliamentary majority and this could a be viewed positively by markets. In the meantime, Mario Draghi’s government will address some of the work on the budget law. When the new government is sworn in, it may choose to make adjustments to public finance figures and try to negotiate a revision to the national recovery and resilience plan (NRRP). It is also likely to stick to EU fiscal targets and avoid clashes with EU institutions on economic policy. Campaign promises are likely to be amended, but some fiscal loosening may be attempted.

- Italy debt market: The better-than-expected performance of Italy’s economy in H1 2022 contributed to a favourable environment for fiscal trends, supporting technical factors. On the demand side, ECB data on sovereign debt as of end-July showed the central bank’s commitment to fighting fragmentation. As such, the ECB role has proved relevant thus far in 2022. Foreign positioning is low by historical standards. At the same time, marginal foreign flows look to be less of a spread-driver than they were in previous phases of rising volatility and uncertainty, thanks to the ECB’s role and rolling investors’ high investment. These factors, together with the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), should help counterbalance the hawkish ECB stance. The BTP-Bund spread proved fairly stable in the run-up to the election. We believe that idiosyncratic risks will stay contained and the spread will be driven by investor confidence in the Eurozone’s economic prospects. Investors may consider raising their exposure to BTPs if the spread returns to the 250bp area.

- Italy equity market: Following the general election, Italy’s equity market should see some short-term relief, rebounding somewhat in the financial sector. From a valuation standpoint, Italy’s market is relatively cheap. In order to see a structural rally, we need more clarity on government appointments, on the final approval of the 2023 budget law, and on possible changes to the NGEU plan that the incoming government may negotiate with the EU. As such, uncertainty surrounding the outlook for Italian equity remains high. We focus on companies that have visibility on future growth, with some protection from strong inflation, and keep a balanced exposure to sectors. If the centre-right coalition sticks to its campaign pledges, we could see some fiscal support to Italian corporates, possibly resulting in some positive impacts for Italy’s small- and mid-cap segment.

What was the outcome of Italy’s general election and what could be the possible scenarios ahead?

The centre-right coalition won a majority in Italy’s general election on 25 September.

In line with opinion polls, the centre-right coalition won a majority in Italy’s general election on 25 September. At the time of writing, local newspapers report the centre-right coalition gaining approximately 44% of votes. What differs from pre-election opinion polls is the distribution of power both within the centre-right coalition and among other parties. At the time of writing, Brothers of Italy performed better than expected, winning over 26% of votes, while the League under-delivered, gaining almost the same share of votes as Forza Italia, with both at around 8- 9%. Regarding the centre-left coalition, the Democratic Party earned some 19% of votes, also under-delivering, while the M5S surprised to the upside, with over 15% of votes. Following the poor result, Democratic Party Secretary Enrico Letta resigned. The centrist alliance of Azione+Italia Viva gained almost 8%, slightly ahead of opinion polls. Election turn out was 63.9%, a record low.

The presidential decree which dismissed the chambers in July and called for the general election also set the date of the first Parliament meeting for 13 October. Following this date, the House of Representatives and the Senate will have to elect their presidents. Only after this, Italy’s President Sergio Mattarella may start consultations to form a new government. On this basis, Italy could have a government as soon as the first week of November (since 1946, the average time to form a government after a general election has been 46 days, with the most recent governments taking longer). Although results are not final yet – especially for seat assignment – two elements emerged from the vote:

- the centre-right coalition is likely to be called to recommend the new prime minister, who would probably be Brothers of Italy’s leader Giorgia Meloni, in light of the party’s net majority of votes within the coalition;

- Brothers of Italy – which finds itself in a much stronger position than its two coalition partners – will need its allies. However, to ensure a solid majority in Parliament, with the more centrist and pro-EU Forza Italia reported to have a similar political weight to the League, which is usually more vocal against the EU. This balancing factor could be viewed positively by markets, especially in light of reassuring messages from Meloni on possible foreign policy developments and in terms of the EU fiscal framework discipline.

The institutional calendar outlined above overlaps with specific deadlines for Italy’s budgetary process, which will see Mario Draghi’s caretaker government doing some of the work on the budget law before the new government is sworn in.

What are the implications for the Italian economy in terms of budget law, recovery plan implementation, and fiscal discipline?

The new government will face stringent deadlines into year-end, especially on the budgetary process and delivery of NGEU milestones and targets. The 2023 budget law includes several deadlines for legislative approval and at the EU level:

- End-September: the caretaker government will publish the update note to the Document of Economy and Finance (NADEF), including new budget and macroeconomic projections.

- The NADEF contains key projections needed to prepare the draft budgetary plan (DBP) that has to be submitted to the European Commission by mid-October.

- The caretaker government has to present a draft of the budget law to Parliament by 20 October so it may be assessed and amended. The newly elected Parliament will go through this process.

- When the new government is sworn in, it may be willing to make adjustments to public finance figures, if significant divergences from those in the NADEF are expected; this could delay the submission of the DBP to the Commission.

- The Commission will issue an opinion on the DBP by 30 November.

- Parliament has to approve the budget law by 31 December.

Brothers of Italy will need its allies to ensure a solid majority in Parliament. With the more centrist and pro-EU Forza Italia reported to have a similar political weight to the League; market could perceive this as positive.

NGEU milestones and targets: Based on the timeline agreed with the Commission, Italy will have to meet 54 goals in order to access some €20bn in funds earmarked for year-end. The caretaker government has progressed with NRRP implementation and plans to complete 29 of these goals by October. Out of these 54 objectives, 15 have been completed or almost completed, three have not been started yet, and the remainder are in various stages of progress. The incoming government will have to ensure the completion of the remaining goals. We expect the Commission to take into account some possible delays due to the election and will grant some flexibility. However, key market concerns remain around the pledge to renegotiate the NRRP that the centre-right coalition highlighted during the campaign. We believe that the Commission’s stance may depend on the new government’s approach. Recently, both the European Commissioner for Economic and Financial Affairs Paolo Gentiloni and the Commission Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis said they were open to limited corrections to the plan. The EU regulation on the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) allows member states to ask for amendments to the NRRP based on a reasonable request to the Commission, which will open a new approval process for the revised plan. As such, a revision to limited parts of the plan – e.g., in order to improve the allocation to energy independence – may be feasible. Yet, it would be key that the revision remains limited and does not push back the implementation of the plan.

Revisions to limited parts of the plan – e.g., in order to improve the allocation to energy independence – may be feasible.

Fiscal discipline: The incoming government is likely to stick to EU fiscal targets and avoid clashes with EU institutions on economic policy, in line with Meloni’s statements (she made reassuring statements on compliance with EU fiscal rules. As such, the new government may have to cut some the campaign promises, especially on the introduction of a flat income tax. Yet, given the economic agenda of the centre-right coalition, some fiscal loosening may be attempted. However, such a task will be made difficult by increasingly narrow fiscal room. Indeed, any change to the Budget Law by the caretaker government will face a deteriorating economic environment. Lower growth and higher interest expenditure may already trigger in the caretaker government’s DBP an upward revision to the 2023 budget deficit, further reducing the fiscal room available to the incoming government.

What is your view on Italy’s debt fundamentals and technicals?

Italian debt technicals look to be supported heading into year-end by several factors.

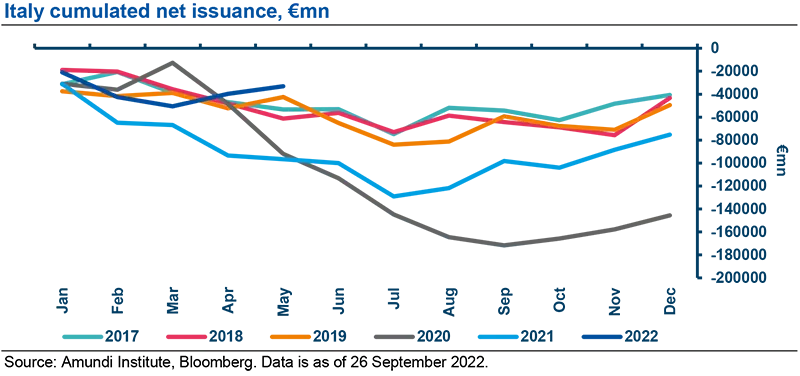

The better-than-expected performance of Italy’s economy in the first part of the year contributed to a favourable environment for fiscal trends, ultimately leading to more resources available for additional fiscal support aimed at mitigating the fallout of the energy crisis, without the need to upgrade the projected deficit. This has been supportive of this year’s technicals compared to the past: on a rolling twelve-month basis, central government borrowing peaked in February 2021. After this, the cash balance has recovered steadily, reducing funding needs compared to expectations, as net issuance stabilised at low pre-pandemic levels this year.

Italian debt technicals look to be supported heading into year-end by several factors. On the supply side, yearly net funding needs were achieved fully in H1, thanks to: strong front-loading of net issuance, a cash surplus in excess of year-end targets, and the approved incoming NGEU tranche, worth an overall €21bn, of which €10bn in grants and €11bn in loans. The cash surplus was almost €100bn at end-July, close to its 2021 peak and roughly €20bn higher than normal levels. These factors ultimately imply that net supply should be negative both in September and in Q4.

ECB data on sovereign debt as of end-July showed the central bank’s commitment to fighting fragmentation across the Eurozone.

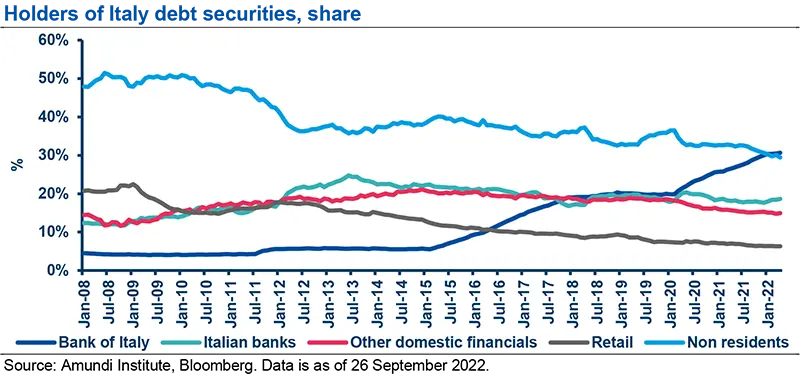

Moving to the demand side, ECB data on sovereign debt as of end-July showed the central bank’s commitment to fighting fragmentation across the Eurozone. Thanks to the extra BTP purchases carried out in July through flexible PEPP reinvestments and worth €9bn, the ECB bought the entire net funding planned for Italy’s debt in 2022. As such, the ECB’s role has proved relevant this year in buying net issuance and achieving a strong role as a rolling investor, despite the PEPP and the APP ending in March and June, respectively. Foreign positioning is low by historical standards: the foreign share of Italy’s marketable debt is below 30%, with exposure probably underweighted in absolute terms as well with respect to pre-pandemic levels, mainly regarding mid- to long-term bonds. At the same time, marginal foreign flows look to be less of a spread-driver then they were in previous phases of rising volatility and uncertainty, thanks to the ECB’s role and rolling investors’ high investment. Indeed, the Bank of Italy – on behalf of the ECB – has become the main holder of Italy’s marketable debt, suprassing foreign investors, while Italian banks’ holdings are not at extreme levels. These factors, together with the Transmission Protection Instrument (TPI), should help counterbalance the hawkish ECB stance over the next few months.

Which factors will you be monitoring over the next few weeks?

Overall, we believe that Italy’s general election result offered no major surprises vs exit polls. At the margin, the news flow is positive, as the centre-right collation will not have a two-thirds parliamentary majority, which would have allowed it to vote for constitutional amendments. At the same time, it has enough seats to construct a stable government. The next factor to watch will be the appointments of key ministers, such as economy and finance and foreign affairs. These appointments should be announced in early November at the earliest, even if some names circulate earlier. On this, we would bear in mind that President Matterella can veto some nominations, as happened in 2018. Another factor to watch closely is the overall government relationship with Brussels on key topics such as the NGEU plan and the EU foreign policy.

How do you expect the Italian debt market to perform? How might the BTP-Bund spread perform over the next few months?

The BTP-Bund spread proved fairly stable in the run-up to the election, thanks to the light positioning from overseas investors and to the ECB’s anti-fragmentation tool. We believe that idiosyncratic risks will remain contained and the spread will be driven by investor confidence in the Eurozone’s economic prospects – when investors become negative on the Eurozone, the euro and BTPs are the clear choice to play a bearish scenario. Investors may consider raising their exposure to BTPs if the spread returns to the 250bp area.

We believe that idiosyncratic risks will remain contained and the spreads will be driven by investor confidence in the Eurozone’s economic prospects.

What is your view on Italy’s equity market following the election outcome? Which sectors you will be focusing on?

Following the general election, Italy’s equity market could experience relief in the short term , with some rebound expected in the financial sector, driven by potential stability in the BTP-Bund spread and rising interest rates. From a valuation standpoint, Italy’s market is relatively cheap, both for large and small-mid caps. The 2022 P/E ratio for the FTSE MIB index is below 8x, with no particular deterioration being seen in EPS revisions. Foreign investors have light positioning on the Italian market. In order to see a structural rally, we will need to see more clarity on government appointments, on the final approval of the 2023 budget law, and on possible changes to the NGEU plan that the incoming government may negotiate with the EU.

As such, uncertainty surrounding the outlook for Italian equities remains high. Against such a backdrop, we focus on those companies that have visibility on future growth, with some protection from strong inflation, and that are keeping a balanced exposure to sectors. Valuations are not demanding for banks and utilities, but short-term prospects remain unclear for both sectors, due to the economic environment and the energy crisis. If the centre-right coalition sticks to its campaign pledges, we could see some fiscal support to Italian corporates, possibly leading to some positive effects for Italy’s small- and mid-cap segment.

We focus on those companies that have visibility on future growth, with some protection from strong inflation, and that are maintaining balanced exposure to sectors.

Definitions

- Asset purchase programme: A type of monetary policy wherein central banks purchase securities from the market to increase money supply and encourage lending and investment.

- Basis points: One basis point is a unit of measure equal to one one-hundredth of one percentage point (0.01%).

- Front loading: Issuing as many bonds as possible at the start of the year, when there is ample liquidity in the market.

- PE ratio: The price-to-earnings ratio (PE ratio) is the ratio for valuing a company that measures its current share price relative to its per-share earnings (EPS).

- PEPP: Pandemic emergency purchase programme.

- Quantitative easing (QE): QE is a monetary policy instrument used by central banks to stimulate the economy by buying financial assets from commercial banks and other financial institutions.

- Quantitative tightening (QT): The opposite of QE, QT is a contractionary monetary policy aimed to decrease the liquidity in the economy. It simply means that a CB reduces the pace of reinvestment of proceeds from maturing government bonds. It also means that the CB may increase interest rates as a tool to curb money supply.

- Spread: The difference between two prices or interest rates.

- Volatility: A statistical measure of the dispersion of returns for a given security or market index. Usually, the higher the volatility, the riskier the security/market.