Summary

Key takeaways

The German economy has been lagging behind other Eurozone countries due to structural changes in its economic model and global trade. A huge investment effort would be needed to relaunch it. Economists recommend making up the lost ground within ten years by making massive infrastructure investments.

A head of February’s election, many parties are proposing to reform the debt brake rule. While a major fiscal stimulus plan should not be anticipated next year, even modest reforms could influence positively investor sentiment, particularly if paired with a new off-budget fund for defence spending.

The Constitutional Court ruling of November 2023 does not rule out the possibility of new off budget funds in Germany. While the court emphasised that special funds must serve their intended purpose, the successful €100bn defence fund established after the invasion of Ukraine implies that similar initiatives could be pursued to address pressing needs.

In Germany, the poor economic performance of the last two years has taken centre stage.

No demand components seem capable of supporting the economy in the short term

The rise in wages recorded in the third quarter is significant (+8.8% YoY), but is primarily the result of one-off bonuses aimed at offsetting past inflation. Greater wage moderation is already perceptible in key sectors such as metallurgy and the labour market has begun to weaken. Exports, industrial production and the construction sector are weighing on economic activity. With the federal elections scheduled for 23 February 2025 political uncertainty should weigh on household spending and business investment at the start of the year, especially as credit conditions remain restrictive. The Bundesbank expects a large number of business failures in 2025.

Not a temporary weakness German real GDP has been stagnating for five years (up by just 0.1% since 2019). The German economy is underperforming the other Eurozone economies because of structural changes. Its automotive sector is in crisis and global trade is no longer as supportive of its exports as it was in the past. Germany is facing a number of challenges simultaneously industrial competitiveness is suffering from rising energy costs and increasing competition from high-quality products from China; the rapid ageing of its population - faster than in the rest of the Eurozone - is also eroding its economy’s potential growth, estimated at 0.8%.

Donald Trump and the threat to the German industry

If tariffs are implemented, they could cost the German economy 0.6pp of growth, according to the Bundesbank. Disagreement over the budgetary measures to be taken to deal with threats and challenges is largely responsible for the break-up of the ruling coalition. The German government forecasts a rebound in real GDP of 1.1% in 2025 (after a decline of around 0.1% in 2024), thanks to the favourable trend in real disposable household income. However, downside risks have increased. The European Commission is more cautious, with 0.7% growth expected in 2025. On 13 December, the Bundesbank revised its own GDP growth forecasts from 1.1% to 0.2% for 2025 and from 1.4% to 0.8% for 2026. This strong revision is intended to encourage an expansionary fiscal policy.

To tackle its investment deficit, Germany should stimulate its economy in the

coming years. A possible reform of the budget rule and an off budget fund for defence spending would be positive steps that could enhance investor sentiment.

A huge public investment deficit

Several German institutes have estimated that the investment deficit amounts to €600bn, representing 14% of GDP in 2024 without taking into account defence spending requirements, which are estimated at €30bn a year (0.7% of GDP). This lack of investment may threaten Germany's future Economists recommend making up the lost ground within ten years by making massive infrastructure investments.

To achieve this goal, the government would need to stimulate its economy by 1.5% of GDP every year, but this is currently impossible due to the debt brake rule. The problem of under-investment is not only linked to a lack of available funds; excessive bureaucracy is also considered to be largely responsible for the backlog of public investment.

An increasingly contested fiscal rule

Germany is currently at a budgetary impasse. Enshrined into the German Constitution in 2009 the debt brake rule limits the structural (i.e., cyclically adjusted) budget deficit to 0.35% of GDP per annum. Suspended since 2020 because of the health crisis, this rule was reinstated in the 2024 budget. In a stagnating economy, there is a need to reform this rule. Several reform proposals, of varying degrees of ambition, have been put forward. With a public debt representing 63% of GDP in 2024 (vs around 110% in France), Germany has a great deal of budgetary leeway to increase investment without putting its public debt on an unsustainable path.

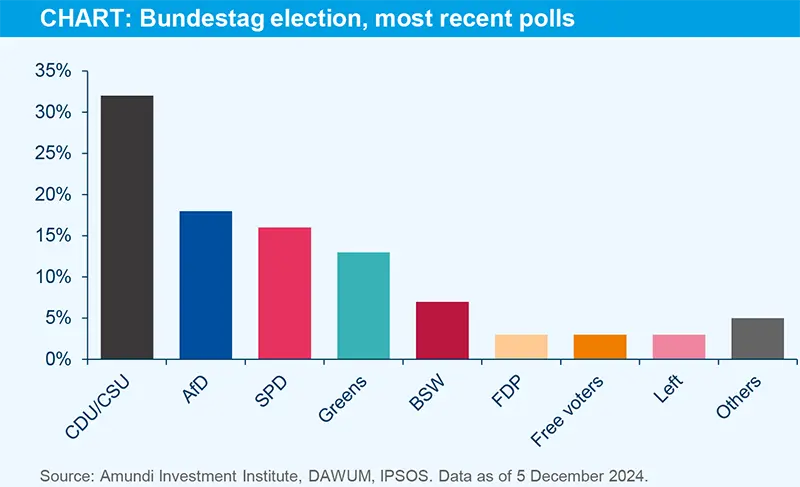

The idea of reforming the debt brake to support investment spending is gaining backing from many parties, with the notable exception of the FDP. The CDU, SPD, and Greens, likely coalition partners according to recent polls, are in favour of this reform (see article on the next page). While a major fiscal stimulus plan may not be anticipated next year, proposed fiscal relaxations could unlock funds equivalent to 0.5% to 1.0% of GDP annually, starting in 2026. That said, even modest reforms could influence positively investor sentiment in 2025 particularly if paired with a new off-budget fund for defence spending.

BOX: Towards new special funds?

In the 2020s, the use of off budget funds increased considerably. According to the Bundesbank, total potential (multi year) deficits in 2022 amounted to €400bn, or around 10% of GDP in 2023. By way of comparison, the debt brake limit would only have allowed borrowing of €13bn in 2023. In federal budget legislation, an off budget fund ("special fund" or "Sondervermogen") is an independent supplementary budget (shadow budget) intended to fulfil a specific function. These special funds, like the budget, need to be passed by a majority of Members of Parliament and are subject to control by Parliament.

These 'off-budget' funds have been used to circumvent fiscal rules, in particular the debt brake. In 2022 the transfer of €60bn of funds intended to deal with the consequences of the Covid-19 crisis to a special Climate and Transition Fund was challenged before the Federal Constitutional Court. In November 2023 the Court declared this reallocation unconstitutional, on the grounds that there must be a direct causal link between the exceptional emergency situation identified and the borrowing limits exceeded. However, it is important to note that the Constitutional Court did not prohibit the use of these special purpose vehicles. It only ruled against the principle of reassignment. In short, for the Constitutional Court, special funds can only be used for the purpose for which they were intended.

It is worth noting that the €100bn special fund set up after the invasion of Ukraine in 2022 to strengthen Germany's defence capabilities was not affected by the Constitutional Court's decision in November 2023. This suggests that a new fund of the same type could be created, for defense or even to finance other needs.

GEOPOLITICS

German elections in focus

There are upsides and downsides to the snap election on 23 February for Germany and Europe. On the upside, a change in government could provide Germany with a more stable government that is able to implement economic and fiscal reforms - such as reforming the debt brake rule, which defines strict limits on government borrowing (see previous article) - and provide stronger leadership in the EU. On the downside, it means that Germany will face more uncertainty at a time when it should be preparing for the impact of the incoming US administration. The snap election also brings the risk of another constrained three party coalition and a strong opposition which could block constitutional reforms.

Despite the downside risks, there is a strong likelihood of an outcome that will be well received by markets. If the CDU/CSU enters into a coalition with the centre-left (SPD) or the Greens, there will likely be a compromise on fiscal reform once in power, as the left-leaning parties would make it conditional on supporting this coalition. The CDU leader and likely chancellor, Friedrich Merz, would probably agree to such a compromise. It is noteworthy that former CDU chancellor Angela Merkel has publicly voiced support for debt brake reform. If the outcome of the election results in a grand CDU/SPD coalition, either debt brake reform or another creative mechanism to inject some fiscal stimulus into the economy seem increasingly likely. This could unleash a reform package that could include more room for public investment, defence spending, a reduction in welfare spending and cuts to business tax.

However, there are also various scenarios under which there would be no fiscal reform and Germany could find itself in the same situation under Merz as it is currently in under Chancellor Scholz. For instance, the CDU may need to enter into another three way coalition including the liberal FDP, and the FDP remains as committed to preventing debt brake reform as it is today, or parties on the far right and left may gain more than one-third of seats in parliament so that they could block the constitutional change needed for debt brake reform.

While the far-right AfD is likely to emerge stronger from this election, it is unlikely to end up in government given Germany’s history.

While the far right AfD is likely to emerge stronger from this election, it

is unlikely to end up in government given Germany’s history.

EQUITY MARKET

German equity market: a rising star in Europe

In 2024 the German DAX index has been a strong performer in the European equity landscape, achieving a notable year-to-date increase of 21% as of 16 December 2024. This performance contrasts sharply with the Eurostoxx 50 which is up 13% (total return), and the broader Stoxx 600 index, which has recorded a more modest gain of 11% (total return).

Beyond its international profile (82% of sales achieved outside of Germany), one of the key factors contributing to the DAX's success, is its sector composition. The index features a significant allocation to industrials (25% of its weighting) and technology (19%). This focus has allowed the DAX to benefit from long-term themes like defence, climate change, and ongoing digital transformation.

Additionally, the DAX's substantial allocation to the financial sector, at 20% has further supported its performance. The financial sector has seen strong gains across Europe this year, and the DAX has effectively capitalised on this momentum. Looking ahead, earnings expectations for the DAX are promising, with projected growth of 11% over the next 12 months, well above the anticipated growth for the broader European market, which is expected to be around 7% according to Ibes.

Our mapping of European country indices positions Germany as a standout. This is, in fact, a cyclical international market that has positive relative EPS momentum compared to the rest of Europe, as well as a positive market trend. Beyond being overbought in the short term, this favourable positioning, combined with its appealing sector composition, is likely to continue to attract investor appetite in 2025. The main risk is the high concentration of the index as just four stocks account for 41% of its market cap.

The DAX's substantial allocation to industrials, technology and financial sectors, combined with a favourable earnings outlook, makes it an appealing market for investors.