Summary

- A steady and downward decline in relations between the US and China in the coming years will lead to limitations in investments and technology cooperation between the US, the G7 and China. Additionally, the war in Ukraine is changing global alliances and many countries’ geopolitical positioning.

- China’s role in talks, and its leverage over Russia, may pave the way for a diplomatic rapprochement, allowing China to showcase itself as a constructive player.

- Irrespective of developments on the battlefield, Ukraine has emerged as a geopolitical force, while Putin’s Russia will continue to shift its attention to the South and the East.

- While the US benefits from being resource-independent, domestic politics are a source of vulnerability. On the flip side, the EU suffers from resource dependencies and geographic proximity to the war but benefits from being a power that both China and the US want to have strong ties to.

- The geopolitical realignment has far-reaching implications for businesses, increasing the prevalence of economic warfare, sanctions and protectionism. In this context, new opportunities may arise in countries with sophisticated technology sectors (such as Japan, South Korea) or a cost-effective labour force (such as Mexico) – also thanks to their proximity to China and the US.

- Mitigating the impacts of geopolitical shifts can be a challenging task: assets with a physical value that is not reliant on financial equilibria – such as gold and potentially oil – can serve as effective hedges against extreme developments.

Geopolitical risks are here to stay

Russia’s incursion into Ukraine and the great power rivalry between the US and China have catapulted investors into a new reality of constant and increasing geopolitical risks. There are two specific events that, should they materialise, would lead to deep ruptures in the global economy and amplify market anxiety:

- A substantial escalation between the US and China;

- An escalation of the war in Ukraine, either beyond its borders or because another global power gets actively involved.

As these risks loom large, investors need to get a sense of how likely they are to happen and how best to prepare. Tensions between the US and China, as well as the war in Ukraine, are accelerating geopolitical shifts, as many countries seek to position themselves for: (i) maximum gain as global powers compete, and (ii) possible military ramifications. The realignments that are underway will raise costs, and require businesses and investors to spend more time navigating and monitoring risks.

In this paper, we explore the nature of US-China relations moving forward, as well as how the war in Ukraine might play out. We will then examine how these realities are affecting geopolitical shifts. Finally, we will examine the possible investment implications.

US-China relations will remain on a downward trajectory

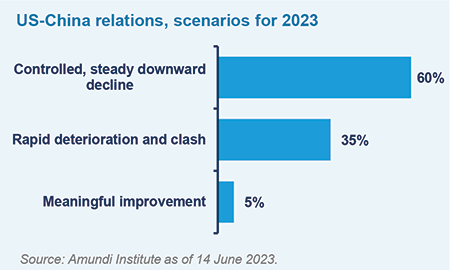

A few years ago, the hawkish view on China that now dominates US politics was a fringe opinion. Over time, the US has become more concerned with China’s alleged behaviour in international commerce and human rights. As China emerged as a challenger to the US’s dominant position in the global order, Democrats and Republicans have aligned their views. With the 2024 US election approaching, being tough on China will remain a campaign focus for all candidates. For example, Republican contender and Florida governor Ron DeSantis recently introduced a law limiting Chinese nationals’ rights to buy property. From a US perspective, US-China relations are likely to continue on a steady, controlled, downward decline.

Recent developments in Beijing echo this. Following the termination of China’s Zero Covid policy in late 2022, a number of events have irritated Beijing, including the shooting down of the ‘spy balloon’, accusations that it was transferring weaponry to Russia, and the dismissal of its peace plan for the Russia / Ukraine war. The historical ‘code of conduct’ of competition suggests that great powers should avoid humiliating one another, as this increases risks. Xi Jinping abandoned China’s hitherto dominant tactic of ‘hide your strength and bide your time’ to emerge onto the world stage as a more assertive global actor. His meetings with Russia’s Vladimir Putin and participation in the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement were intended to display China’s influence in global affairs.

The desire to ‘play nice’ with US politicians has waned. Xi Jinping’s speeches emphasise national security over economic concerns. At the same time, China is eager to boost its economy and entice foreign investors. These competing streams are causing uncertainty and sending mixed signals.

Despite the political tensions, neither the US nor China benefits from a direct confrontation, and both are well aware of this. Therefore, we expect the relationship between China and the US to remain on a controlled downward trajectory over the coming years.

Nevertheless, the fallout from the downside materialising is so large that both sides have to prepare for it. The US needs to signal that it would not accept Chinese action against Taiwan by expanding its military presence in the region, while China needs to signal that it is militarily capable of standing up to the US.

The current arms race illustrates that the US and China are playing a high-risk ‘game of chicken’, that will at times mimic aspects of the Cold War. In game theory, this game is a constant provocation strategy in which the optimal outcome is that one player yields to avoid the worst outcome if neither gives. Each player provokes the other to increase the risk of humiliation for the one who yields.

The advance of nuclear weapons made the cost of war so high that it reduced the prevalence of direct warfare between great powers. The ‘overkill’ effect puts great powers off from direct war compared to previous periods in history where direct war was often the most likely outcome in the competition between great powers. However, while nuclear weapons serve as a deterrent, the animosities of competition between great powers can lead to accidents, miscalculations, and human and machine errors that can lead to conflict.

New technologies, such as AI, which will be exploited by malign actors, add a significant unknown layer to the list of the things that could go wrong. Importantly, however, this is not Cold War 2.0, but a high-stakes competition in which both sides depend on each other. China is deeply intertwined with the world economy and the US, whereas the Soviet Union was not.

The US and China are playing a constant provocation game in which the optimal outcome is that one player yields to avoid the worst outcome if neither gives.

What will the status quo of a ‘controlled downward decline’ in US-China relations look like?

Our base case of a controlled, downward decline does not exclude temporary episodes of improved relations. This year is likely to be relatively calm, with rays of sunshine in US-China ties, as the two sides will hold a number of high-level meetings in the months ahead. However, there will be some negative developments, as the US prepares to announce new controls on investments to China, and drives G7 countries to comply. Many US allies will refuse to fully support the US’s strategy towards China, but will likely agree to limit investments and cooperation in some areas such as semiconductors, quantum computing and artificial intelligence. The US will increasingly focus on limiting cooperation with China in sectors that can aid China’s technological and military advancement.

At the same time, the US and its allies will endeavour to shore up domestic industries and industry in other countries that help it diversify away from China. Full diversification is extremely difficult, and therefore unlikely, but diversification in sensitive industries is more feasible. To this end, the US and the G7 will court countries in Latin America, Central Asia and India. There will be a renewed appetite to forge trade and security agreements, such as efforts to revive the Mercusor trade deal. On the other hand, China will increase its global influence to offset US efforts by courting some European countries in order to compensate for the technological loss from the US. China will increase its involvement in regional security and economic arrangements, such as those in the Middle East. It will also continue to penalise some Western companies in response to US export controls, enhance support for the most vulnerable domestic industries and increase investments in high-tech priority areas.

The Russia-Ukraine war is still changing global alliances

This year, the Russia-Ukraine war became a new factor weighing on US-China relations. In a worst-case scenario (not our base case), the war could see more active involvement from China (and, indeed, turn into a proxy war). However, it is more likely that China’s involvement will lie in resolving the war and its leverage over Russia could pave the way for a diplomatic rapprochement, allowing China to showcase itself as a constructive geopolitical player. This would boost EU-China relations and is therefore in the latter’s interests. To counterbalance the US, China will remain close to Russia, but it won’t go so far as to undermine its relations with other important partners.

There are several scenarios for how the war could play out over the coming months. Ukraine’s counteroffensive will be crucial. Today, ceasefire negotiations in the second half of the year are somewhat more likely than prior to the Wagner insurrection in Russia: various elections in 2024 (in the US, EU, and in the UK) will increase pressure on Ukraine to negotiate before elections risk undermining Western support. Conversely, recent events have shortened Putin’s timeline. While he will remain firmly in the driving seat, the element of doubt over his stronghold on power will undermine the notion that ‘time is on his side’. Simply waiting for Western support to wane while continuing to erode Ukraine’s limited manpower now risks making Putin more vulnerable over time. A ceasefire will likely be predicated on conditions that neither side will find easy to accept.

Regardless of developments on the battlefield, and at the negotiating table, there are a few certainties:

- Ukraine has become a geopolitical force;

- Ukraine’s army is Europe’s best-trained, armed and battle-tested. Leaving Ukraine outside of NATO and the EU would constitute a risk to security;

- Under Putin, Russia will be unable to return to the status quo that existed between the 2014 invasion of Crimea and the 2022 invasion of Ukraine. Even if some sanctions against Russia are lifted following a peace deal, the atrocities committed in Ukraine mean Putin will remain a persona non grata in many Western countries, fuelling Russia’s ambition to gain influence in the East, Africa and Latin America.

A new geopolitical order is resulting from the war and US-China tensions

The international response to the war in Ukraine has alarmed some Western capitals, as many countries have avoided denouncing Russia and joining the EU and the US in imposing sanctions. When the UN General Assembly voted against Russia’s actions in Ukraine earlier this year, 32 countries abstain, including China, India and South Africa. Meanwhile, Russian officials are still welcome in Africa, Latin America, India and the Middle East.

The so-called ‘Global South’ has become impatient with the US and EU’s ‘obsession’ with the Ukraine war, while conflicts in other regions of the world go largely ignored. There is anger at the expectation that economies should accept the economic and security implications from condemning Russia, without getting any support in return. This has caused resentment among many leaders in Africa. Simultaneously, countries at the frontline of a potential US-China clash in Asia fear for their security, while ‘old’ US allies in the Middle East feel neglected as US focus shifts to China. Others in Latin America see the friction created by the US-China competition and the war as an opportunity.

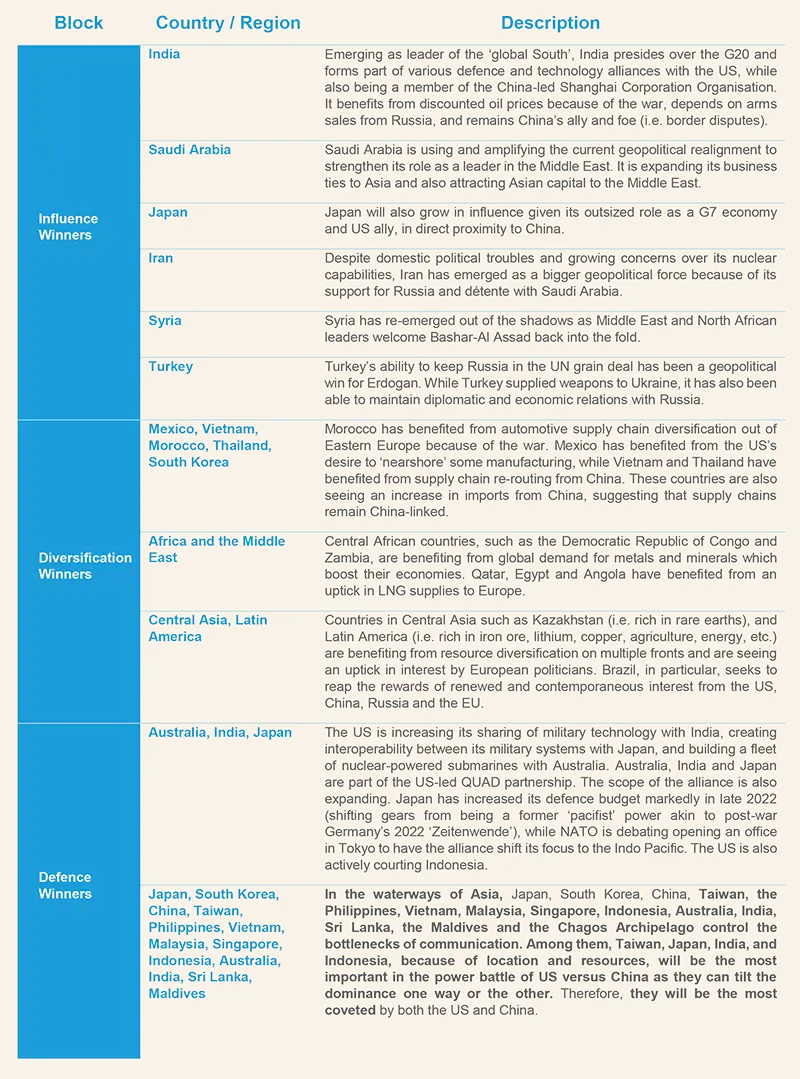

Regardless of their rhetoric, most political leaders will continue to avoid taking sides. Countries that are ‘flirting’ with other powers (South Africa and Saudi Arabia, for example) are not actively shifting away from the US. Many countries with strong ties to China, such as Indonesia and Vietnam, are also apprehensive about China, while others, which have refrained from condemning Russia, such as India, are not actively backing it. These countries will attempt to capitalise on the emerging ruptures in order to achieve their own strategic and commercial goals. They can roughly be classified into the following blocks; some countries will overlap categories and emerge as ‘winners’ on multiple fronts.

- Influence winners: Countries that have increased their geopolitical influence because of the war in Ukraine and US-China tensions, such as Saudi Arabia, Brazil, India, Japan, Turkey, and Iran.

- Diversification winners: Countries benefitting from the diversification away from China and Russia thanks to their natural resources, allowing for immediate (i.e. energy) and future (i.e. rare earths) diversification, or countries benefiting from strategic geographic locations for supply chain diversification.

- Defence winners: Countries benefitting from defence agreements with the US, such as the Philippines, Japan, Australia, South Korea, India, Taiwan and Singapore.

However, where there are winners, there are also losers:

- Those ‘left behind’ by the shift in focus caused by the war and US-China tensions include Belarus, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Serbia;

- As the US shifts away from the Middle East, Iran’s nuclear programme increases risks for Israel and makes it more likely that Israel will strike at Iran’s nuclear programme, potentially causing a new conflict in the Middle East;

- Countries such as Japan, South Korea and the Philippines could be more impacted if US-China tensions escalate and these countries become military frontlines;

- Countries being ‘forced’ to move supply chains or are caught up in China’s economic measures, which target countries that voice criticism against China;

- Resource-poor countries and geographically less advantaged countries, which are suffering from high prices and are unable to take advantage of the drive to diversify resources;

- The Arctic could become a new frontier for competing powers seeking to expand their influence and access to resources, increasing geopolitical tensions in a region made more accessible because of global warming.

Implications of these shifts for key actors of the war and the great power competition

If the war ends within the next year or so, Ukraine will likely be able to solidify its global prominence as a defender of Western ideals and democracy over autocracy and hasten EU accession proceedings. With or without full NATO membership, Ukraine will remain militarily linked to the West and will serve as the EU’s de facto defence against future potential Russian aggression.

While some re-engagement is likely in the future, as most wars end in diplomacy, Russia under Vladimir Putin will remain focused on the East and South, seeking to strengthen its alliances outside of the G7. When Putin leaves the scene, a rapprochement with Russia will become more likely.

China will begin to feel the effects of export controls in critical sectors. Should the economy continue to struggle, Xi Jinping is more likely to focus on security issues and foreign affairs as a result.

The war benefits the US in sectors such as defence, energy and agriculture, and has given it greater leverage over the EU. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) will cause a ‘brain drain’ from Europe as firms transition towards the US. Because the US is more resource-independent than Europe, it will be less vulnerable should countries exploit natural resources to gain geopolitical advantage. On the flipside, US influence has waned in relative terms as other powers have stepped up. The US’s main weakness lies in its domestic politics, concerns relate to the return of former president Donald Trump to the presidency in 2024 and the collateral damage caused by tensions with China for the economy and businesses.

Given its dependence on resource imports, proximity to the war and pressure to align with the US against China, the EU is squeezed by the present geopolitical upheavals. At the same time, the EU has a few advantages:

- In terms of the green transition, the EU benefits from a comparatively more sophisticated regulatory environment and political system than the US: its consumers and firms are more attuned to the need to tackle climate change. Even if the IRA threatens Europe’s competitive edge, the context for accelerating the green transition remains favourable, supported by its need to reduce existing energy dependencies.

- The war has also reignited the desire to broaden the EU’s geographic scope, with a shift in attitude towards the idea of Eastern European states, including Ukraine, joining the EU;

- When it occurs, the reconstruction of Ukraine will likely boost growth in Europe, since European businesses will be most involved;

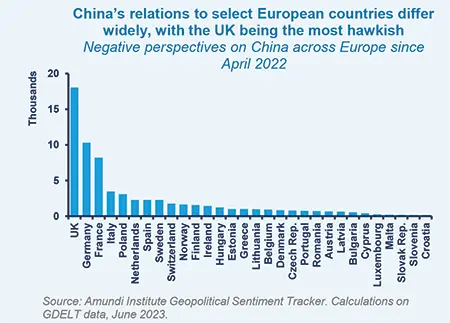

- While EU member states will align with the US on restricting Chinese access to certain sectors, there are differences in the degree of hawkishness towards China. Most European states will remain open to engaging with China, particularly as the US election looms large. As global powers compete, the desire to win over global leaders will benefit the EU, making it an appealing business destination for Chinese investments, compared to the US.

What are the broader implications?

- Economic warfare, export controls and sanctions will become more prevalent. Sanctions on major powers have grown increasingly acceptable in the context of rising US-China tensions and the Russia-Ukraine conflict;

- Increasing economic warfare, sanctions and the struggle for global influence raise the risk of a ‘hot’ war, particularly proxy wars;

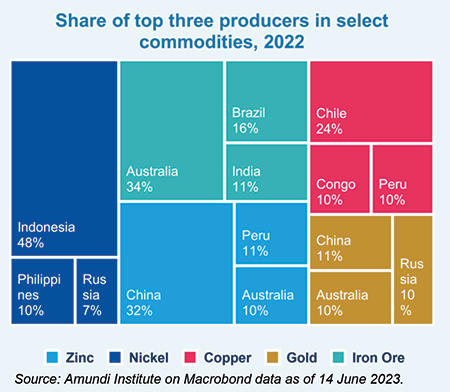

- Natural resources will likely be exploited to gain political advantages (as seen with oil and gas, and as has occurred throughout history). China’s control over rare earths and dominance in solar infrastructure are noteworthy;

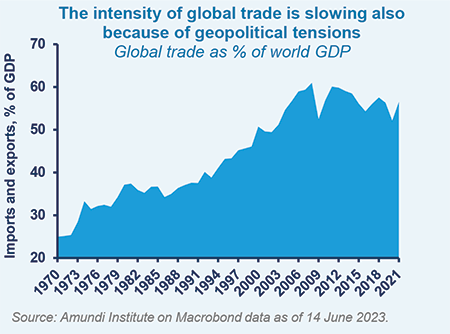

- Protectionism and nationalist industrial policies will increase (as has already been seen in the US and the EU), eroding the scope for mutual cooperation;

- Rule setters will continue to ignore the rules (WTO rules, the US, China) undermining the rulebook for all;

- As the IMF pointed out, greater geopolitical tensions threaten financial stability.

As individualistic strategic and political interests trump the notion that fewer trade barriers are good for common prosperity, this ‘each to their own’ approach will make doing business more complex, ineffective and costly, while risks will increase. Politicians and business executives will be busier than ever navigating their international exposures.

Geopolitical realignments are reshaping investment flows

The ongoing geopolitical realignments have significant implications for investments across sectors. While our central scenario remains that of a controlled disengagement and slowdown in the relationship between China and the US, events can escalate rapidly, leading to a rapid chain reaction. In response, companies are proactively taking measures to mitigate risks rather than waiting for escalations to happen. For example, by reducing their dependence on Chinese suppliers and diversifying their sourcing and production strategies. These shifts have reshaped and shortened supply chains, and altered investment flows. Moving forward, we expect a shift to more regional markets, accompanied by a redefinition of investment flows.

These shifts will also create new opportunities in different regions. For instance, countries such as Japan and South Korea, which are closer to China and possess a high stock of technology, can intercept additional investment flows resulting from relocations. Mexico stands to benefit from the relocation of industries, as US and European companies move to capitalise on its cost-effective labour force and proximity to the US. Additionally, the US is actively re-evaluating its relationships with countries such as Thailand and Malaysia, which can be instrumental for shipping within the region. Furthermore, Europe is exploring the possibility of striking a Mercusor trade agreement with Latin America, potentially altering the way commodities and other goods are sourced in the short term.

In our view, five sectors are at the epicentre of the current geopolitical movement: semiconductors, electric vehicles, biotech, and AI. Companies developing cutting-edge technologies within these sectors will enjoy a competitive advantage. Export bans on these technologies, especially those with military applications, aim to hinder China from gaining a technological advantage. From a top-down perspective, the fear of sanctions will rift international flows and alter the market landscape.

While there may be some structural demand for Chinese assets stemming from Europe, subdued demand from US investors weary of possible sanctions is likely to regionalise the flows, reflecting the geopolitical equilibrium. Nevertheless, China remains an interesting prospect from the perspective of European investors, particularly if Europe remains less affected by the evolving geopolitical dynamics and sanctions.

China’s appeal lies in its development as the second largest economy in the world, with relatively low per-capita income, and its potential for endogenous, regional and self-contained growth, which can lead to growth in specific market segments ranging from consumption to personal insurance and healthcare. Moving forward, investors may view China less from the perspective of a fast-growing economy and more as an entity that wants to credit itself as a major superpower. This perception is also reflected in the cautious monetary approach adopted by Chinese policymakers. Rather than pursuing ultra-accommodative monetary conditions, they are prioritising stability, preserving valuations and resisting the temptation to flood the market with liquidity despite the prevailing low level of inflation. Moreover, China is trying to make the most of a world that is attempting to ‘de-dollarise’ to some extent due to the geopolitical forces discussed.

Investment opportunities despite challenges

Europe faces its own set of challenges, as corporations contemplate relocating their production to the US given its less stringent labour market regulation, lower commodity costs, a similar interest rate cycle, and incentives for tax reductions in specific sectors. These potential relocations may catalyse future problems. The response of European countries to challenges posed by geopolitical tensions, high inflation, elevated energy prices and increased input costs will significantly influence the region’s trajectory. However, fractures within Europe are becoming increasingly apparent, with countries behaving far more opportunistically. Italy, for example, has started supplying China with intermediary components for biotech, as evidenced by a sudden surge in its net exports to EUR 9bn in March 2023.

In the current environment, we see two drivers profoundly affecting the investment landscape in the developed world in the near future. The first is the environmental transition. Europe will likely heavily employ its fiscal powers, as well as regulatory measures such as MiFID II to maintain a competitive advantage. This approach will pave the way for a substantial deployment of private capital towards the most virtuous companies, thereby fostering the transition. The second driver is artificial intelligence, which poses significant regulatory questions. There is a risk that European corporates may face limitations in leveraging the development of these technologies due to regulatory challenges, potentially widening the productivity gap with less unionised markets such as the US.

While geopolitical shifts introduce volatility and uncertainty, they also open up new avenues for investments. Looking ahead, the overall environment is expected to become more inflationary. A fundamental approach to investing will be crucial, as companies start to reassess their cost structures to effectively navigate the changing landscape and shorter supply chains. During this transition, certain commodities may become locally scarce. For instance, since December 2020, Indonesia has banned raw nickel exports, urging foreign buyers to invest in local smelters to process materials before export. Similar measures are being considered for bauxite and cobalt.

This strategic move aims to redesign Indonesia’s industrial policy, by positioning the country a couple of notches higher up the value chain. Moreover, Indonesia’s plan to establish a domestic electric vehicle battery industry envisages imposing taxes on ferronickel exports, thereby providing lower-cost inputs for Indonesian industry.

Following this example, commodities afford countries newfound bargaining powers they haven’t previously enjoyed, enabling them to attract local production sites, also thanks to their more cost-effective labour force, in exchange for providing commodities. This presents a unique opportunity for some emerging market economies to step up their positioning along the value chain, transitioning from being predominantly commodity exporters to producers of intermediary goods. Mitigating the impacts of these geopolitical shifts represents a challenging task, as they involve gradual transitions rather than sudden, extreme events. In situations where there is a complete disruption in growth patterns, assets that have a physical value – such as gold and potentially oil – can serve as effective hedges. During such significant disruptions, there is a natural inclination to seek real assets that maintain their intrinsic value even in times of uncertainty.