Summary

The Fed has started shrinking its balance sheet as part of its fight against elevated inflation. However, QT is being challenged by the Fed’s new role as a counterparty of money-market funds. The process would be greatly improved if the Treasury were to announce a debt buyback financed by the issue of T-bills.

The Fed’s QT as a component of the fight against inflation

As part of its fight against elevated inflation, the Fed has raised its key rates very rapidly in 2022 and in June began to shrink its balance sheet by non-reinvesting a portion of its maturing agency MBS and Treasury securities.

As a reminder, the Fed currently holds $2.7tn of MBS and $5.6tn of Treasury securities. One of the motivations behind the process of shrinking the balance sheet, known as ‘quantitative tightening’ (QT), is the fact that the Fed pays an interest rate on some liabilities: the reserves held by commercial banks and the reverse repo agreements, operations under which the Fed borrows overnight, mostly from money-market funds (MMFs). Recently, the cost of the Fed’s liabilities has increased sharply and outpaced the earnings on its assets. These ‘losses’ could grow if the Fed continues to raise its key rates and if it maintains them at a high level for some time to come. Another motivation of QT is to regain room of manoeuver for ‘quantitative easing’ (QE) in the future.

A major difference with the previous episode of QT (2017-19)

Embarking on QT is not unprecedented for the Fed. It also did so from end-2017 until September 2019, when a crisis emerged in the US repo market. By then, too much central bank money had been destroyed by QT, money-market rates went out of the Fed’s target range, and the Fed had to come back to a ‘technical’ QE from October 2019.

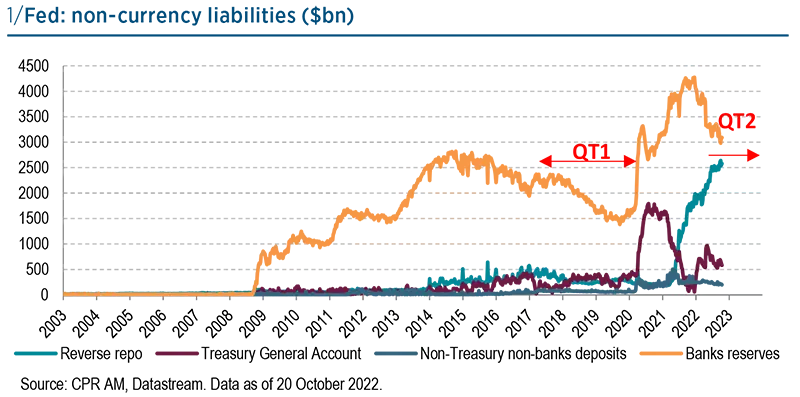

A large difference between the current QT and the 2017-19 one relates to the composition of the Fed’s liabilities: its reverse repo agreements account for around $2.5tn currently, vs. very small quantities during the previous QT episode. While in 2017-19 QT could only lead to a reduction of commercial banks’ reserves held at the Fed, nowadays it could theoretically also lead to a reduction in the Fed’s reverse repo agreements. This is due to a shift in US MMFs over the past three years.

The Fed’s quantitative tightening cannot work in its current format

The impressive rise of US money-market funds

Assets under management (AuM) of US money-market funds (MMFs) exploded with the Covid-19 crisis and have held up since (at some $5tn), because of the persistent economic uncertainties and the accumulated excess savings of households and corporations. Taking a little more historical perspective, we see that MMFs’ AuM increase when key rates are high (or rise) and then deflate in the years following a recession, when key rates are still low and when more attractive investment opportunities appear. This did not happen in this cycle, possibly because the phase where rates remained low was short compared to other cycles. The fact that the Fed has kept raising its Fed funds target range in 2022 – and will possibly do so next year as well – is more likely to boost the MMFs’ AuM, rather than lower them: a recent note1 from Fed economists estimated that they would increase by $600bn by end-2024.

A lack of investment opportunities for MMFs

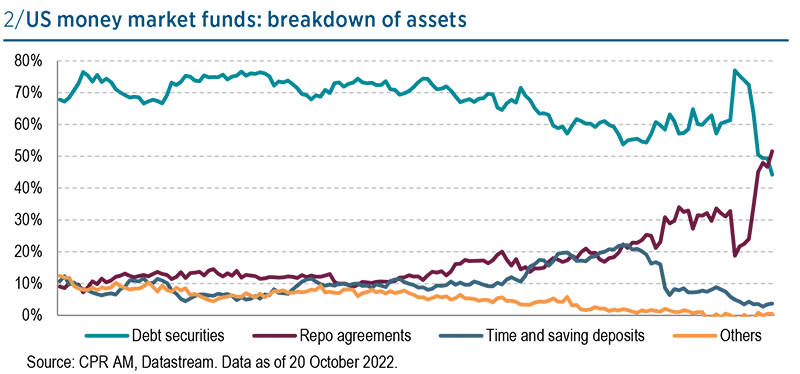

MMFs’ AuM should therefore increase, but these funds have had fewer and fewer investment opportunities because of the sharp reduction in the outstanding amounts of T-bills by the US Treasury over the past two years (the stock of T-bills has fallen by approximately $1.5tn over this period)2. At this level, something new and rather extraordinary is happening, since the majority of MMFs’ assets, which have historically been invested in debt securities, are now made up of repo agreements, almost exclusively with the Federal Reserve as counterparty. The average maturity of MMF portfolios collapsed with the greater weight of repo agreements with the Fed.

In Q2 2022, it was the very first time that over half of the assets of US MMFs consisted of repo agreements. This was facilitated by the Fed, as it had twice raised the limit per counterparty of its reverse repo agreements ($180bn currently) and as it had raised the interest rate on reverse repo agreements in June 2021 compared with the lower end of the Fed funds target range. At that time, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell argued that the move was necessary to “provide a floor for money-market rates and help ensure that the federal funds rate stays within the target range”. In other words, it was supposed to be a technical measure in the face of the explosion of liquidity the Fed had created with its QE operations. By doing so, the Fed initiated a new role as ‘borrower of last resort’, whereas central banks are known for their traditional role as ‘lender of last resort’ instead.

The Fed has initiated a new role as ‘borrower of last resort’

The ‘impossible’ QT that FOMC members want

Getting back to the Fed’s QT, it seems that there is a form of consensus among FOMC members on the fact that the ‘excess of excess liquidity’ to be purged corresponds to the amount of the Fed’s reverse repo operations, possibly because they are uncomfortable with this new role as ‘borrower of last resort’. For QT, FOMC members may prefer to see a decrease in reverse repo agreements instead of a decrease in the commercial banks’ reserves. In a recent speech, a New York Fed official3 expressed confidence in the fact that QT would lower the amount of reverse repo agreements over time as “greater certainty about the economic outlook and the path of policy may also moderate demand for the shortest tenor money market instruments”.

This may sound like wishful thinking, as there are clearly no signs of a decline of MMFs’ AuM for the time being. Consequently, the amounts of reverse repo agreements have gone up strongly, while commercial banks’ reserves held at the Fed have fallen sharply since the start of QT. If this trend were to continue for some time, some localised reserves shortage might reappear at some point, as happened in September 2019.

The necessary coordination with the US Treasury

In reality, the Fed’s QT cannot work in its current format. For reverse repo operations to fall sharply, the US Treasury would have to change its issuance strategy and issue much more T-bills. This may ultimately be what will happen – with the aim of improving liquidity on the Treasury market, the US Treasury has begun asking primary dealers whether it should buy back securities with longdated maturities by issuing T-bills. This would be a great way to run QT without lowering the reserves held by commercial banks too far and too fast. In short, a possible announcement of Treasury buybacks would be positive for financial markets. Ultimately, this shows that monetary policy cannot work properly nowadays without coordination with the Treasury.