Beyond the impact of domestic economic variables, euro rates are determined by the energy crisis and political monetary choices. The combination of a new regime of higher energy prices and persistent expansionary fiscal policy could lead to a debt supply shock and persistent inflationary pressures.

The energy crisis will be the main economic drivers in Europe

- Economic growth is slowing. The slowdown will accelerate in 2023 with the end of the Covid-19 catch-up effect, the impact of higher production costs, and the cumulative effect of monetary tightening. Leading indicators already point to recession in the United Kingdom and Eurozone.

- The key question for investors remains the impact of lower economic activity on inflation. The economy is in a better position in the United States than in Europe, as US inflation is mainly demand-driven, while Eurozone inflation is cost-driven. Indeed, in the Eurozone energy-price inflation, at 41.5%, remained the main driver of headline inflation.

- The price of energy in Europe could remain high and volatile for longer, if Russia pipeline flows do not resume. In recent weeks, gas prices have dropped in a context of high storage levels and mild temperatures. EU gas storage sites are now 95% full, above their five-year average. Even medium-term prices are down, but the outlook for next year remains challenging. The process of filling EU storage sites over the summer of 2022 benefitted from two factors that might not be repeated in 2023: (1) Russian pipeline flows during the summer; and (2) lower liquefied natural gas imports by China due to its economic slowdown and Covid-19- induced lockdown. It is important to note that non-Russian pipeline suppliers have limited upside potential. Thus, if Russia pipeline flows do not resume, Europe will compete with Asia for the supply of its liquefied natural gas. If China returns to the market more aggressively, Europe could find it far more difficult to plug the supply gap.

In the medium term, the combination of a new energy regime and persistently expansionary fiscal policy could lead to a debt supply shock and persistent inflationary pressures

- The EU has implemented expansionary fiscal policies to limit the impact of the energy crisis. Since the start of the energy crisis, €573bn has been allocated in the EU, of which €264bn earmarked by Germany alone, according to Bruegel. Fiscal support limits the downside impact on economic activity by preserving household purchasing power and limiting production cost increases for businesses.

- However, if the energy shock is not temporary, these expansionary fiscal policies present two drawbacks:

- Expansionary fiscal policies would encourage inflationary pressures by encouraging second-round effects on non-energy prices.

- European governments will encounter difficulties in financing their measures, especially in a context where the central banks would begin to reduce the support they are providing.

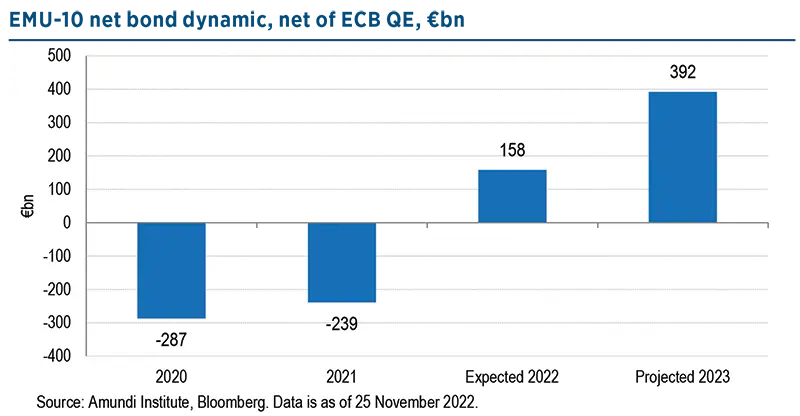

- It is important to note that the ECB ended its support for the euro rate market in mid-2022. In 2015-22, the ECB absorbed all new financing needs of Eurozone countries. In the short term, the risk is limited. Eurozone governments have accumulated cash since end-2019. General government liquidity deposit at ECB amounted to €578bn as of October 2022 (about €250-300bn before Covid-19). In the medium term, one can wonder about the capacity of the euro rate market to finance governments’ needs if the crisis persists and if the fiscal support is maintained.

The combination of a new energy regime and persistently expansionary fiscal policy could lead to a debt supply shock and persistent inflationary pressures.

In this scenario, the ECB would be in a tough position

A central bank has few tools to fight cost-driven inflation, as rate hikes have no direct impact on energy prices. ECB monetary policy tightening aims at keeping inflation expectations anchored and avoiding a depreciation of the euro, which would fuel inflationary pressures. In case of persistent high inflation, the ECB could have to make a trade-off between inflation and financial stability. However, central banks will only be credible when implementing dovish surprises, if inflation rates progress satisfactorily towards the targets. Otherwise, the risk is that this more accommodating tone will be accompanied by greater pressure on the currency and inflation expectations.

Net debt issuance excluding ECB flows will jump to €390bn in 2023 from €160bn in 2022.

Beyond the impact of domestic economic variables, euro rates are impacted by the energy crisis, the Fed’s monetary policy, and political-monetary choices

Risks of a severe recession pose some downside risks to yields. However, the impact of persistent high energy prices is likely to lead to both persistent inflationary pressures and a much looser fiscal policy stance. Thus, beyond the economic variables, the euro bond market depends on:

- Exogenous variables: pressure from Fed rate hikes on the euro and energy prices.

- Political choices: the EU’s fiscal support and the ECB’s potential trade-off between inflation and financial stability.

We foresee the terminal rate at 2.5% and the ten-year Bund yield increasing in the range of 2.3-2.5%.

Government deposits held at national central banks are still above €500bn, more than double the pre-pandemic levels.

Jump in net bond issuance net of ECB flows in 2023 to €390bn from €160bn in 2022

Our initial projections for next year point to an overall volume of EMU-10 countries’ net bond issuance close to €390bn. This means an increase by roughly €30bn compared to net bond issuance expected in 2022, which is estimated to be close to a cumulated €360bn level by year-end. In terms of area breakdown, among EMU-10 countries, dynamics point to an increase in funding for overall core countries and to slightly lower levels for periphery ones.

Most focus is on the dynamics of net funding, net of ECB flows. We are coming from strong QE support, since between 2015 and 2022 the purchases of the ECB cover much more than the net issuance of sovereign bonds of the EMU-10. This year, although purchases ended in H1, ECB absorption of net funding should be close to 56% of EGB yearly net issuance (or €200bn) and of a higher share of overall additional market debt, on the back of negative volumes of bills net issuance year to date.

The level of uncertainty in forecasting next year supply looks higher than in past years. Risks are high of both downside revisions: (1) Possible rise in needed fiscal support at the national level, (2) Possible start of QT and the upside, (3) Treasuries use of accumulated cash, (4) T-bills issuance.