Summary

Executive summary

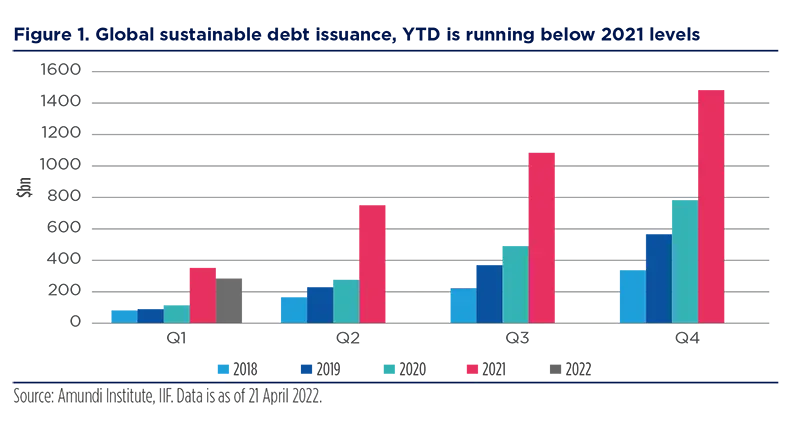

Last year global sustainable debt issuance hit a record of over $1.4tn, with the overall sustainable debt universe expanding to near $3.4tn. In the first quarter of 2022 this healthy trend halted temporarily, as high energy prices and rising borrowing costs weighed on market trends. We believe this setback should prove transitory and that the sustainable debt market remains on track to exceed $4tn by mid-2022, as the Russia- Ukraine war should reinforce the trend towards sustainable investing. We believe the current geopolitical tensions could be a catalyst for political will to step up the Net Zero transition, as reducing the dependence on fossil fuels may emerge as a national security priority in support of energy independence in some jurisdictions.

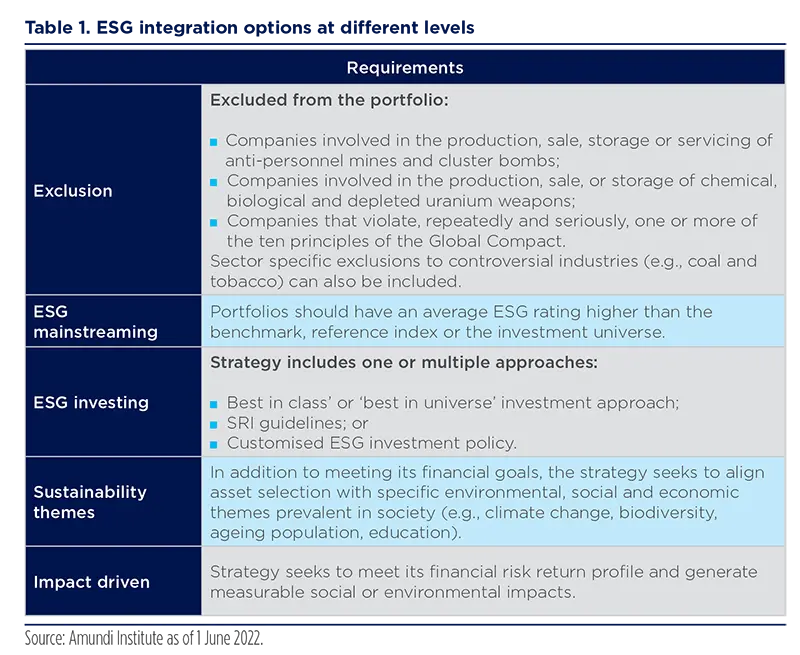

This evolution will bear important consequences for ESG fixed-income investing as a whole, even if in this article we focus mainly on credit markets. While early bird institutional investors started to incorporate ESG criteria in their portfolios some years ago, the trend intensified in 2021 with the Covid-19 crisis and the introduction of the new Sustainable Finance Disclosure (SFDR) regulations in Europe which encourage investors to opt for more ESG transparency. Nowadays, the most common ESG integration policy in fixedincome portfolios has evolved from an exclusion-only policy to a more articulated set-up, which combines an exclusion policy with some form of quantitative ESG scoring (ESG is going mainstream). We think that investors should go beyond this quantitative approach and apply materiality as a way to reconcile quantitative scoring with qualitative credit assessments for effective and well-rounded ESG portfolio integration. This will help identify short- and long-term risks to prevent any security impairment, while pursuing relative-value opportunities.

This approach should be complemented with an effective engagement policy between issuers and investors. If applied on an ongoing basis this could encourage companies to adopt best ESG practices, while challenging them on the ESG risks they may face. In addition, ESG reporting between investors and final clients is key, and part of our duty, as it showcases the investor’s commitment and facilitates opportunities for dialogue with clients on an ongoing basis.

Some specific considerations need to be applied when dealing with securitised assets, due to their specific nature. Here, the debate focuses on whether it is more appropriate to consider the compliance of the pool of assets or to assess ESG compliance at the originator level, considering its ESG policies and the use of proceeds obtained from the sale of loans. Focusing ESG analysis on the collateral may leave holes in the risk detection and magnify ESG risks in the balance sheets of entities holding the worst assets. In the end, it may paradoxically prevent the development of these virtuous assets. As such, it needs to be complemented with an ESG assessment of the originator.

In summary, we believe that the journey of ESG integration into fixed income portfolios has been a long one, but much remains to be done. Large institutional asset managers could play a key role in facilitating the integration of ESG principles into fixed-income investment processes. The next steps include the extension of ESG integration to other fixed income assets and to non-traditional issuers, further development of labelisation and being active regarding the Net Zero goal.

ESG in fixed income markets: trends and prospects

An accelaration in the sustainable debt market

Last year was a milestone for ESG investing in fixed income markets. Helped by robust investor appetite, global sustainable debt issuance hit a record of over $1.4tn in 2021, almost double the 2020 pace, according to the Institute of International Finance (IIF). In Q1 2022 issuance took a hit, falling nearly 20% compared to Q1 2021, as higher energy prices, the Russia-Ukraine war and rising borrowing costs weighed on market trends. Green bond issuance dropped to around $110bn, the slowest issuance volume since Q4 2020. The slowdown was driven by the government sector, while corporate issuance remained robust. In the same vein, social bond issuance picked up in Q1 to around $33bn, up from $23bn in Q4 2021. Sustainability bond issuance was also up by 25% YoY, led by suprationationals and sovereigns.

Despite this transitory setback, sustainable debt remains on track to exceed $4tn by mid-2022, with the United States, France, Germany and China accounting for around 40% of the total market. Emerging markets (EM) are filling the gap with developed markets (DM). The EM sustainable debt universe expanded to over $525bn, with some $54bn issued in Q1 2022. Activity was concentrated in China, which raised around $32bn during the first three months of 2022, mostly via green bonds. Excluding China, EM issuance mostly came from Latina America and EM Asia ex-China, notably the Philippines and India.

Increasing investor appetite for responsible products

The increasing awareness of the relevance of ESG criteria on the issuance side has been met with enthusiasm by investors. While the topic of ESG integration has mostly involved equity markets for a long time, the first ESG-compliant fixed income portfolios date back to the late 1980s. At that time, such portfolios featured strong ethical backgrounds, often with emphasis on the social pillar. Institutional investors were among the first to dig deeper into ESG fixed income in the 1990s, complementing their standard investment policy with a new approach based on engagement and excluding those issuers fairing badly on ESG considerations. New ESG tools have emerged since then – including green, social, sustainability and, sustainability-linked (GSSS) bonds. They can help portfolio managers pivot their investments towards the energy transition and address the main social issues faced in a post-Covid-19 world. Another route contemplated and used by investors and asset managers is mainstreaming, which not only targets impact and thematic investments through GSSS bonds but applies to whole portfolios or balance sheets.

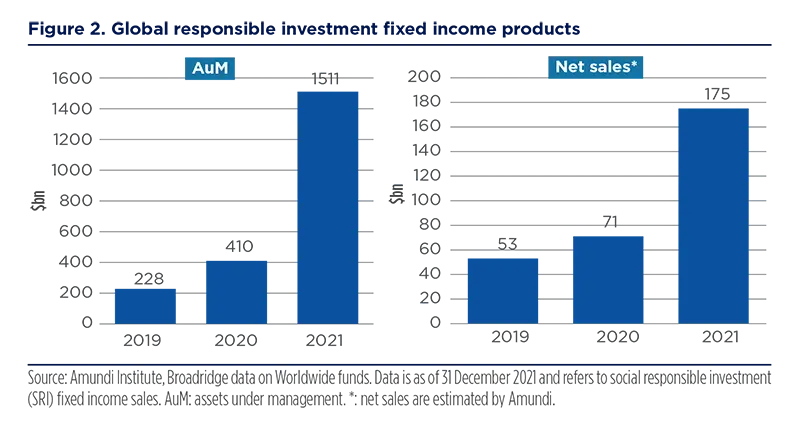

This has led to a strong growth of assets under management (AuM), featuring diverse attempts to encompass all ESG dimensions into portfolio management and has contributed to innovation: the growth of Socially Responsible Investment (SRI) products exceeded $1.5tn in AuM last year. In 2021, estimated net sales of such products were $175bn, more than doubling the pace in 2020.

ESG tools such as green, social, sustainability and sustainability-linked bonds can help portfolio managers pivot their investments towards the energy transition and address the main social issues faced in a post-Covid-19 world.

This has invariably been accompanied by a large – sometimes too large – breadth of investment approaches, helped in some areas by a lack of specific definitions in terms of regulatory requirements. Initially, this led to the development of several labels, at the national level, as a way to address the regulatory aspect, but also to meet the willingness of investors and regulators to develop advanced reporting standards to showcase accountability and transparency. To harmonise disclosure requirements, the EU SFDR was introduced in 2021, leading to a full reshape of the European ESG landscape. SFDR is a set of rules which aim to make the sustainability profile of funds more comparable and better understood by investors.

At the same time, several academic works have assessed the performance contribution of integrating ESG criteria into portfolios, cementing in investors’ minds the financial interest of pursuing this path. Our in-house research has shown the improving performance of ESG investing in 2010-19 in the corporate bond market. This means that we are moving from a world where ESG integration was a way of limiting the drawdown risk to one where ESG principles can add value to investments. The potential to generate alpha lies in possible inefficiency areas, where market prices do not fully integrate all relevant information, which is often the case when it comes to ESG dynamics. Nowadays, several years after the ESG integration first began and since Milton Friedman's statement in 1979: “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits”, the financial community has made significant progress. Over the past ten years, ESG integration has moved from a ‘nice-to-have’ to a ‘must-have’ approach. This trend has followed different paths across markets, reflecting their specific features. Also, the approach has evolved from a static one to a dynamic and forward looking one, reflecting the development of Net Zero strategies which aim to ensure the future trends of companies regarding the Paris Agreement’s goals. Finally, new central bank (CB) mandates – which may include green bonds in their asset purchase programmes – could help finance the green transition and subsidise carbon spending. This should enhance further growth potential of the ESG fixed income market.

We are moving from a world where ESG integration was a way of limiting the drawdown risk to one where ESG principles can add value to investments.

Focus: green bonds could take a core-allocation role for euro-based investors amid market growth

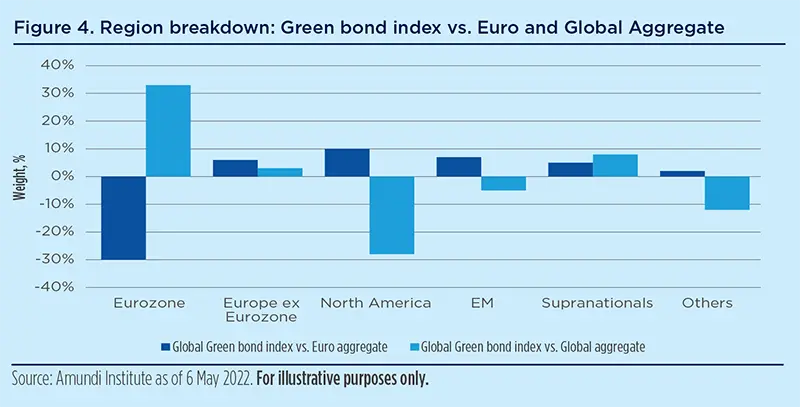

For euro-based investors, the Global Green Bond index (euro hedged) could be an alternative to traditional core bond indices (Euro and Global Aggregate, euro hedged). In fact, it has delivered similar performance since inception (January 2014) to the other benchmarks, while offering wider diversification than the Euro Aggregate index and a greater European focus compared to the Global Aggregate.

Regarding diversification, the green bond market represents a well-diversified universe that can be appealing to euro investors. It enjoys lower sovereign exposure and a higher allocation to agency, supranationals and corporates compared to the other two benchmarks. The corporate overweight is mainly in those sectors which are key to the energy transition (e.g., utilities, banking and real estate). From a geographic and currency standpoint, the Global Green Bond index has higher diversification than the European benchmark thanks to its global reach, while it is less dollar-centric and more euro-tilted than the global benchmark. The dominance of euro issuers in the green bond market is mostly due to the EU’s advanced transparency rules and the European green framework.

Finally, a comparison of the three indices shows that the Global Green Bond index has a higher average duration than the other two indices (7.7 for the former, 7.2 for the Global Aggregate index, and 7.0 for the Euro Aggregate index) and enjoys a higher yield (1.79% versus 1.54% for the Euro Aggregate index and 1.25% for the Global Aggregate index).

Key features of ESG investing in credit markets

The ESG approach to fixed-income markets has evolved over time. Investors started by using exclusion policies, that is excluding companies that do not comply with their own ESG policy, international conventions, internationally recognised frameworks and national regulations. ESG integration then stepped up and was adjusted according to the different fixed income markets it applied to. The following analysis focuses on the ESG approach applied to credit markets.

Nowadays, the most advanced investors in credit markets adopt an ESG approach which combines an exclusion policy with some form of ESG scoring.

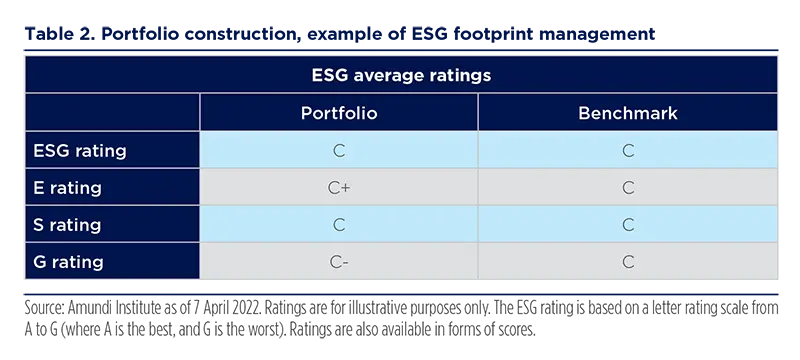

Nowadays, the most advanced investors in credit markets adopt an ESG approach which combines an exclusion policy with some form of ESG scoring. Our ESG integration process centres on three approaches:

■ Exclusion, applying our exclusion policy of G-rated issuers, with G being the lowest available score;

■ Quantitative, with scoring (ESG mainstreaming) and a ‘beat-the-benchmark’ approach, to get an average ESG portfolio score higher than the benchmark; and

■ Qualitative, with materiality.

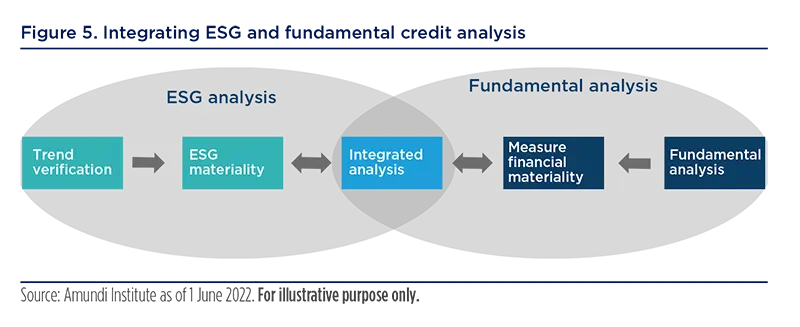

The ESG scoring process is based on the identification of a set of relevant criteria for each sector and a deep dive on such criteria through the application of expert judgment. Investors should go beyond the quantitative approach and apply materiality as a way to reconcile quantitative scoring with qualitative credit assessment.

ESG rating analysis provided by our internal ESG research team

Our ESG rating analysis is based on a ‘best-in-class’ approach. This methodology consists of rating companies based on their ESG practices according to the specific sector they operate in. Each rating can range across a scale of A to G, with A being the highest available rating for those companies which apply the best practices and G the lowest one to reflect the worst practices. Our ESG rating methodology starts from the analysis of multiple extra financial data providers. To be effective, the ESG analysis should focus on key criteria depending on the business. The weightings ascribed to each criterion are key to the analysis. The higher the risk a company faces on any given criteria, the stricter ESG analysts should be on the quality of its practices. The final ESG rating is the weighted average of the scores for each of the three ESG pillars (environment, social and governance). Each pillar’s rating is itself the weighted average of the ratings ascribed to the criteria included under the pillar. In the end, companies are awarded a single overall rating, on an A-to-G scale. The rating is sector-neutral, which means that all sectors are handled equally. Our proprietary ESG ratings are updated on a monthly basis. Company news is followed closely and any controversies or alerts are analysed in order to keep the analysis up to date. The methodology is adjusted according to the evolving environment and to the available news flow. Currently, we cover around 99% of the euro credit market and 97% of global credit markets. Measuring the overall ESG footprint with deep transparency is key to portfolio construction.

Moving to a comprehensive approach means incorporating the ESG-identified factors into a robust credit research framework to help identify both short- and long-term risks to prevent any security impairment while pursuing relativevalue opportunities.

For the credit research team: materiality matters, the risk dimension of ESG

Investors will need to integrate an ESG scoring methodology, such as the one described above, with fundamental credit analysis for an effective and well-rounded ESG portfolio integration. Moving to a comprehensive approach means incorporating the ESG-identified factors into a robust credit research framework to help identify both short- and long-term risks to prevent any security impairment while pursuing relative-value opportunities. The underlying principle is to understand how ESG factors could affect the value of a certain issuer’s debt. To do that, investors should focus on issues such as materiality, for instance, what is the effect on credit metrics and credit value? This task is made more difficult by the fact that, as opposed to equity, fixed-income investors face several challenges that could compound the impact of ESG risk. In detail:

■ Maturity: the credit risk materialisation cycle linked to ESG may take some time to come to the fore and, as such, may not always be relevant to short-term securities, as opposed to longer-term ones issued by the same issuer.

■ Credit quality: higher credit quality is generally better insulated from business risks stemming from different sources, with ESG-related issues being one of them.

Our materiality approach consists of four steps:

- Based on our ESG sector analysis research, we highlight for each sector the most impactful topics and identify the most crucial ESG issues as far as their impact on credit metrics is concerned;

- We analyse the issuer’s business or financial metric profile irrespective of ESG issues;

- We analyse the issuer’s ESG profile by establishing materiality based on the most impactful ESG factor for each sector, as established in step 1; and

- We explicitly layer the ESG impact of the issuer’s business profile and, whenever possible, we assess the impact of its financial metrics in an attempt to establish if those ESG issues are relevant in the credit context.

This approach’s goal is to make full usage of the ESG information delivered by the scoring process, since focusing purely on the rating may capture only one dimension, as the rating is the average of E, S and G pillars, while, when conducting credit analysis, investors may also be interested in the tail risks identified by each criterion. For credit research, every element has its own impact on credit metrics and poor performance in one area could be a threat to the overall credit quality. If serious, poor ESG practices may threaten credit quality or result in a lower internal rating than the issuer might otherwise receive. Hence, the ESG rating will be an input into the business profile rating. The ESG weight in the business profile is up to each analyst to assess and will vary according to sector and materiality. Needless to say, ESG needs to be evaluated in terms that actually alter the metrics and value of the issuer’s debt. If ESG issues are not expected to weigh on financial metrics or on the business profile enough to affect the internal rating, the conclusion is that they are not material. Materiality is measured as the ESG relevance on the fundamental, standalone internal rating of the business profile. The effect on credit metrics and value is the acid test of materiality. The threats and benefits of ESG can impact the following measures: revenue, profitability, cash flow, debt and leverage. The impact can be minimal (less than 5%), moderate (5-10%), or elevated (above 10%). We can also assign these categories to the ESG analysis without an explicit estimate of the financial impact. Some minimal impact should not affect the business profile rating, while a moderate impact will have a variable fallout on the rating. An elevated impact should decrease or increase the business profile rating by at least one notch. A combination of ESG and fundamental credit analysis can help assess the sustainability and profitability of any corporate’s business.

If serious, poor ESG practices may threaten credit quality or result in a lower internal rating than the issuer might otherwise receive.

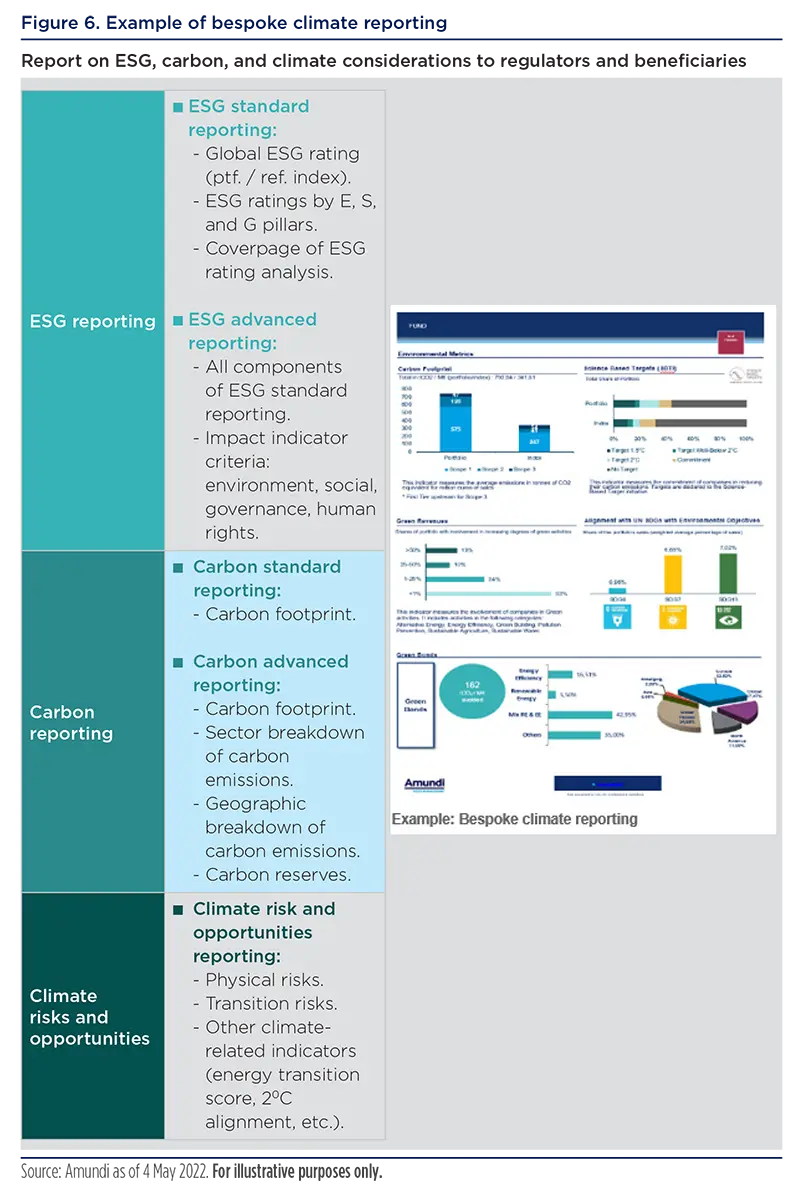

Engagement process

The engagement policy is key, as it could facilitate a productive dialogue between bond holders and companies. If applied on an-ongoing basis, it could encourage companies to adopt best ESG practices and challenge them on the ESG risks they may face. An engagement through influence is also possible, based on an active dialogue with companies on specific themes, making recommendations and measuring their progress. This is all the more crucial for fixed-income markets, as, unlike shareholders, bondholders do not have specific voting rights. The ability to address issues with senior management based on an ongoing dialogue is key for fixed-income investors. A key tool within the engagement process is dedicated reporting, as it allows the investor’s commitment to show through and generates regular dialogue with clients on a continuous basis on these topics.

Reporting

Providing ESG reporting is part of our duty and a way to put ESG at the heart of our investment decisions. By providing ESG reporting, we aim to show our commitment to our key performance indicators (KPIs). Going beyond minimum reporting requirements and showing value to investors requires the selection of measurable KPIs and to leverage on digital solutions to ease the data challenge. The unsatisfactory quality of post-issuance reporting and a lack of transparency are the reasons often cited by clients for reducing or halting their investments in GSS bonds, stressing once more the relevance of ESG reporting.

The ability to address issues with senior management based on an ongoing dialogue is key for fixed income investors.

Case studies

Major Japanese insurer

A Japanese insurer was willing to invest in the ESG theme, not knowing at the beginning whether they wanted to go down the mainstream or thematic / impact route. After due market sizing and intense discussion and training with their ESG team, they decided to go for the thematic/impact route, as they had several managers to whom assets under management (AuM) were delegated – hence, not always fully compatible frameworks – and their mind was not already set on the how, mainstreaming-wise. As a consequence, we set up a portfolio which invested across the global credit universe, targeting green, social and sustainable bonds (GSS), while leveraging our credit and ESG research to ensure a rigorous selection process. This portfolio was heavily geared towards green bonds given this market’s depth, with the possibility of increasing its investments in social and sustainable bonds along the way. The last step was to provide proper reporting designed around the client’s needs.

Major UK fiduciary

A leading global consultant fiduciary team was looking to revamp their selection of asset managers and appoint one centralised manager with the expertise to manage across the entire credit spectrum, while encompassing strong ESG integration. We were selected as the partner to tailor this solution thanks to our track record of delivering consistently strong risk-adjusted returns across every credit sub asset-class. Within this project, the full integration of the consultant’s bespoke ESG framework with individual data requirements was achieved, while complementing our own data resources where required. A key role was covered by our reporting expertise and ability to oversee various KPIs at both a sub-credit asset class and at a global fund level. The flexibility to add additional asset classes (e.g., EM local-currency debt, securitised debt, etc…) as required by the consultant in response to their evolving allocation needs was also key.

Defining our ESG approach to securitised assets

In a public securitisation, the originator – typically a bank or a specialised lender – sells assets to a special purpose vehicle (SPV), generally a pool of loans. These loans are often granted to households or small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and may be backed by a secured interest (e.g., real estate, cars). To fund the purchase of these loans, the SPV issues notes, which are purchased by final investors. To meet the investors’ risk-return goals and optimise the cost of funding, different classes of notes, called tranches, are issued. The cash flow obtained from these assets is allocated to the different classes of notes in compliance with waterfall rules defining priorities.

Regarding ESG analysis on securitised assets, the main debate is focused on whether it is more appropriate to consider compliance of the pool of assets, e.g., whether the loans are ‘green’ or ‘brown’, or alternatively to assess ESG compliance at the seller level, considering its ESG policies and the potential virtuous use of the proceeds obtained from the sale of loans. The first option – assessing the collateral from an ESG perspective – seems relatively straightforward as securitisations have optimal features for such an approach since they benefit from transparency on the pool of assets which back the issuance. For instance, it seems relevant and easy to consider a pool of mortgages with a higher share of the best Energy Performance Certificates (EPC) as more beneficial for the environment than a pool with worse EPCs. However, there are four limits to that approach:

■ Focusing on the assessment of collateral leads to only some features of a deal being considered and ignores potential issues regarding ESG practices during the production of goods, the origination or the servicing of loans.

■ Necessary information to apply such analysis is not always available and sellers may find it difficult to identify and monitor specific assets to a high ESG quality.

■ Sellers may be reluctant to sell their best assets from an ESG perspective, leaving the worst ones on their balance sheets or concentrating them in non-virtuous future securitisations. If all ‘green’ assets are pooled in dedicated transactions, one may find it difficult to attract investors for the remaining purely ‘brown’ securitisations.

■ Finally, selecting only virtuous assets reduces the size of eligible pools, possibly below a minimal threshold to warrant the economic viability of transactions. For instance, the market share of plug-in electric cars rose in 2021, but it still only represents 19% of the entire automobile market, of which just 10% is accounts for electric-only cars. Since they are not available in sufficient amounts, only including virtuous assets in pools of securitisations may paradoxically restrain their development.

In a nutshell, focusing ESG analysis on collateral may leave holes in risk detection, be more difficult to implement than expected and could magnify the ESG risks on the balance sheets of the entities holding the worst assets. In the end, it may paradoxically prevent the development of these virtuous assets.

Similarly, limiting the ESG assessment to the seller and its practices seems insufficient as well, because each pool is specific and may concentrate the worst assets. Ignoring the ESG quality of assets may also be irrelevant, as the goal of transitioning to sustainable growth is to develop such virtuous assets and, ultimately, obtain pure pools of virtuous assets. A comprehensive approach will be needed to overcome these limitations, encompassing the analysis of the originator and its practices, as well as the assessment of the pool of assets used as collateral.

Focusing the ESG analysis on the collateral may leave holes in the risk detection, while being more difficult than expected to be implemented, and magnify ESG risks in the balance sheets of entities holding the worst assets. In the end, it may paradoxically prevent the development of these virtuous assets.

ESG assessment of originator

ESG analysis of an originator is the same as the one used for other bond issuers. Ratings determined under the Amundi methodology are used for this assessment. In some cases, these originator ESG ratings may be not available, e.g., for a boutique collateralised loan obligation (CLO) asset manager. In such cases, a specific questionnaire is used to assess the firm’s ESG policies. The first part of this questionnaire is focused on the originator itself. Currently, it includes 58 main questions, relating to nine themes: exclusion policy, sustainability strategy and priority themes, reducing footprint, staff management, remuneration policy and gender equality, board, business ethics, audit and risk, and cyber security policy and data protection. For each question, E, S or G factors are considered. Examples:

■ E: CO2 emissions, energy consumption, waste, pollution, etc…

■ S: working conditions and non-discrimination, health and safety policies, etc…

■ G: board independence, code of ethics, compensations, shareholders rights, etc…

Similarly, lending practices – or investment practices in the case of CLOs – are assessed through a second part of the questionnaire. It includes up to 25 questions covering seven topics: origination practices regarding individual customers, SMEs / corporations / selfemployed where applicable, servicing, late arrears/borrower management, complaints handling, ESG data and reporting, and ESG integration issues. The two parts of the questionnaire are used to evaluate the ESG assessment of the originator.

For securitisations backed by real estate, the ESG assessment is driven by the environment pillar by comparing the energy efficiency of the buildings.

ESG assessment of collateral

Collateral assessmentis performed in accordance with its nature. For securitisations backed by real estate (e.g., RMBS and commercial mortgage-backed securities, CMBS), the ESG assessment is driven by the environment pillar by comparing the energy efficiency of the buildings: EPC for residential properties, Building Research Establishment Environmental Assessment Method (BREEAM) and Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certifications for commercial properties. The social dimension is assessed through the specific origination criteria which may have been applied to the pool. Social lending is assessed positively, but subprime and nonconforming assets are excluded.

For securitisations backed by car loans and leases, the environmental pillar is also key. It is assessed by comparing the share of hybrid and electric vehicles in the securitised pool against the corresponding share in the European market. To account for the development of these vehicles and their increasing share in Europe, the years of production are distinguished.

For consumer loans and credit card pools, which are widespread and include low-income households, the social dimension is relevant. The quality of the pool is defined by comparing the income structure of borrowers included in the pool with the overall income structure of the country. A higher share of low-income borrowers in the pool than in the country as a whole should provide more financial support to these households and may lead to a better social rating for the pool. However, such a favourable assessment is conditioned by the exclusion of predatory lending practices. These practices are detected through a lending practices questionnaire and the verification that the highest interest rate paid on the loans is not excessive. An overall ESG rating is obtained by combining both originator and collateral analysis. Similarly to other credit bonds, a seven-level scale summarises the security’s ESG quality. The average portfolio rating is calculated as a weighted average of these synthetic ratings. This methodology can be applied to a benchmark for comparison to implement and monitor a ‘beat the benchmark’ ESG process.

Conclusion

Responsible investing was the starting point for our investment policy, accompanying its evolution in the asset management industry from a risk-only dimension to form an integral part of an asset management’s fiduciary duties. As shown, the journey of ESG integration into fixed-income portfolios has been a long one and much still needs to be done, as it remains at the initial stage for the asset management industry as a whole.

A key beneficial and positive impact of ESG integration is that companies are willing (or required) to provide more and more ESG disclosure and to use specific fixedincome instruments to assess their sustainable strategies. This information is key in order to discriminate companies based on ESG criteria and to build dedicated fixedincome strategies on specific themes such as climate change or social inequalities. We believe three key steps have yet to be achieved:

■ Enlarging this approach to other fixed-income assets and non-traditional issuers – such as SMEs or EM bonds – to finance the energy transition, promote the development of innovative market instruments and new approaches, such as ESG improvers, and facilitate market access for small companies.

■ Further development of labelisation.

■ Being active with regards to the Net Zero goal, both in developing measures to evaluate the impact on climate change of investments and shaping them.

A key beneficial and positive impact of ESG integration is that companies are willing to provide more and more ESG disclosure and to use specific fixedincome instruments to assess their sustainable strategies.

Definitions

■ ABS: Asset-backed securities. These are financial securities such as bonds, which are collateralised by a pool of assets, possibly including loans, leases, credit card debt, royalties or receivables.

■ Agency mortgage-backed security: Agency MBS are created by one of three agencies: Government National Mortgage Association (known as GNMA or Ginnie Mae), Federal National Mortgage (FNMA or Fannie Mae), and Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp. (Freddie Mac). Securities issued by any of these three agencies are referred to as agency MBS.

■ Basis points: One basis point is a unit of measure equal to one one-hundredth of one percentage point (0.01%).

■ CLO: Collateralised loan obligation. It is a single security backed by a pool of debt. CLOs are often backed by corporate loans with low credit ratings or loans taken out by private equity firms to conduct leveraged buyouts.

■ Green bonds: A green bond is a type of fixed-income instrument that is specifically earmarked to raise money for climate and environmental projects.

■ GSS bonds: Green, social, and sustainability bonds.

■ GSSS bonds: Green, social, sustainability, and sustainability-linked bonds.

■ MBS, CMBS, ABS: Mortgage-backed security (MBS), commercial mortgage-backed security (CMBS), asset-backed security (ABS).

■ RMBS: Residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) are a debt-based security backed by the interest paid on loans for residences. The risk is mitigated by pooling many such loans to minimise the risk of an individual default. ■ Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): They are businesses whose personnel numbers fall below certain limits.

■ Social bonds: Social bonds are use-of-proceeds bonds that raise funds for new and existing projects with positive social outcomes.