Summary

Executive summary

India’s strong demographics and role in the geopolitical arena make it a long-term opportunity for global investors.

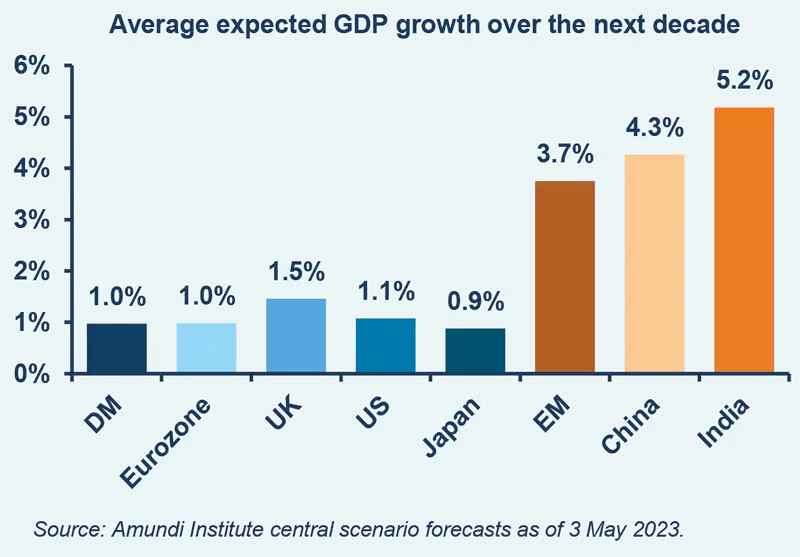

India’s macro fundamentals are well positioned for a multi-year improvement in economic output and earnings. Beyond the long-standing strength of its demographics, urbanisation and rising middle class, new factors are emerging that will accelerate investment opportunities in the country. Indian corporates have deleveraged and now sit on strong balance sheets, banks have strong capital adequacy ratios, and the government has plugged loopholes in the real estate sector. Future policy efforts should focus on green-field investments in newer sectors and industries and should propel the growth of corporate capital expenditure which has lagged in the past decade. The overall outlook for the next ten years is positive, but there are risks to be aware of, particularly regarding politics and policy, geopolitical developments and the evolution of commodity prices.

Looking at the short term, India's growth performance has been strong since the country’s full reopening, with domestic demand and private investments driving the recovery. Although inflation is notably erratic and hard to predict, particularly owing to the food component, the current environment is conducive to lower inflation, with the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) at the end of its current tightening cycle. Meanwhile, the process of fiscal consolidation is ongoing: the path ahead is more gradual compared to pre-pandemic targets, but a commitment to a 4.5% deficit target by FY26 remains.

India's recent economic success has raised hopes of it becoming a global growth engine, but recent market turmoil associated with domestic political developments is casting a shadow over expectations. In spite of its domestic woes, India's influence in the geopolitical arena is likely to strengthen, as it has maintained relationships with various powers and is benefitting from the Western resolve to disentangle itself from China.

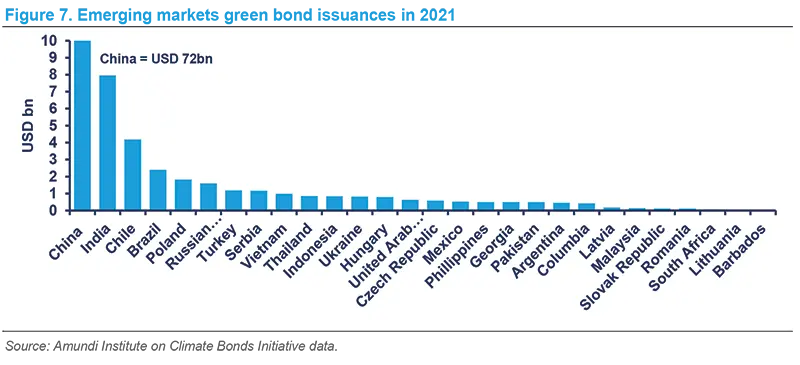

There are several opportunities for foreign investors looking to gain exposure to India. Fixed income yields remain attractive both on a relative and an absolute basis. Although India’s inclusion in global bond indices has been hindered, there are several routes investors can follow to enter the bond market. The Fully Accessible Route (FAR) remains the best for gaining exposure to Indian government securities, whereas the Voluntary Retention Route (VRR) is preferred for corporate bond investments. India's green bond market is also rapidly growing to include public sector organisations, state-owned commercial banks, corporates and the banking sector, with USD 7.45bn issued to date.

Looking at equities, India's long-term growth story is appealing beyond its short-term valuation excess and is supported by improved bank balance sheets, sound corporate balance sheets, leaner cost structures, policy reforms and Production-Linked Incentives (PLI). The Indian rupee now appears more stable and can benefit in an environment of USD weakness. Despite the uncertainty, 2023 may be a better year for the rupee than 2022.

Long-term view: India to see investment-led growth this decade

India cannot be decoupled from the global growth trajectory. Prospects of a slowdown in global growth and tighter financial conditions will weigh on the country’s growth dynamics, contributing to weaker exports and investment activity. Nevertheless, once the global headwinds fade, India can post a strong rebound: its macro fundamentals are well positioned for a multi-year improvement in economic output and earnings.

The typical long-term story for India focuses on its demographics, urbanisation, digitalisation, rising middle class, and consequently the size of wallets. The country is home to 1.3-1.4bn people or 18% of the world’s population. Moreover, the median age of its population is likely to remain below 30 this decade, whereas the median age in China is already 38 years, and 32 years for the world as a whole. This improves the availability of labour and helps contain labour costs, thereby feeding the country’s growth potential. Just over a third of Indians live in urban areas, but over the next few decades, cities will likely experience a greater influx and will benefit from improved access to water, electricity, internet, and urban amenities. Indian household income is likely to double from the current USD 1,700 per capita (estimated for 2022) to USD 3,400 per capita by FY30, leading to better lifestyles and higher discretionary spending. Even though it will benefit from its demographic dividend, it’s fair to say that India needs to keep growing at a relatively fast rate in order to accommodate the significant number of young people who enter the labour force each year.

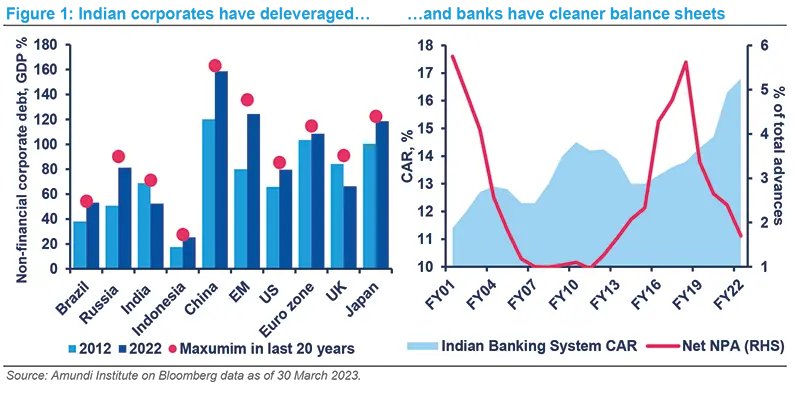

These features were already in place during the past ten years, and their roots date back even before that: assuming political stability, they will help propel growth for many years. But the strength of balance sheets makes an even more compelling case to remain invested in India. Over the last decade, Indian corporates have deleveraged. Corporate debt-to-GDP has dropped significantly from 71% in 2012 to 52% in mid-2022. During this time, corporates in other key nations increased their leverage, with debt positions reaching near multi-year highs. Meanwhile, issues regarding stressed assets in the Indian banking system have been ironed out. Banks now sit on strong capital adequacy ratios (CAR) of around 16% and have a high propensity to lend. Net non-performing assets (NPA) have diminished from the 5.6% high of five years ago to 1.7% in March 2022. During Covid-19, significantly lower interest rates, tax incentives on real estate purchases in select key states, accumulated financial savings among the upper-middle classes, and investments in the property market drove a healthy buying of residential real estate. Coupled with lower residential launches by developers, these helped sort out the longstanding issue of inventory overhang in the system. While today the inventory overhang stands at around 12-13 months (compared to 33 months in 2018), the actual inventory of ready-to-move-in flats barely exists. On top of this, the government has plugged the loopholes in the real estate sector by introducing and improving the Real Estate Regulation Act of 2016.

In summary, Indian businesses had a robust investment cycle from 2004 to 2011 (barring the period of the Great Financial Crisis, GFC). However, the cycle also created lots of excesses in the system. These have now been reined in, giving Indian corporates and lenders a relatively clean slate and a stronger appetite for risk.

Policy in the coming decade should not focus solely on “old” sectors, but on catalysing green-field investments in newer sectors and industries as well.

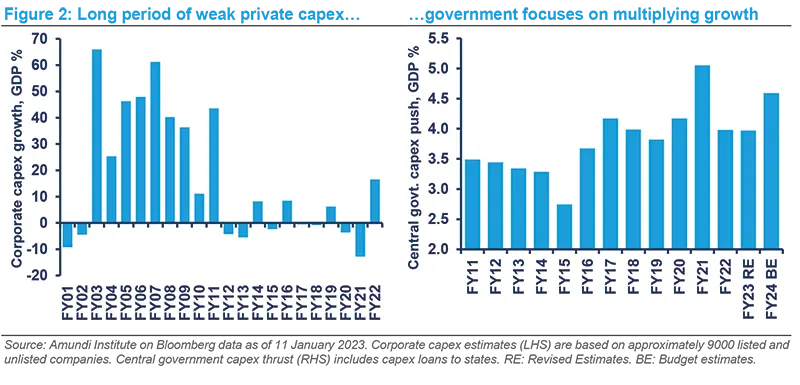

Corporate capex growth, estimated as the purchase of fixed assets by approximately 9,000 listed and unlisted companies, has been almost zero in the past ten years (versus a 41% compound annual growth rate – CAGR – during FY03-FY11). Long periods of low investment in a growing economy have created the need for investment. Capacity utilisation in capex-heavy sectors such as refining, metals, cement and autos has reached levels requiring fresh investment. Policy in the coming decade should not focus solely on ‘old’ sectors, but on catalysing green-field investments in newer sectors and industries as well.

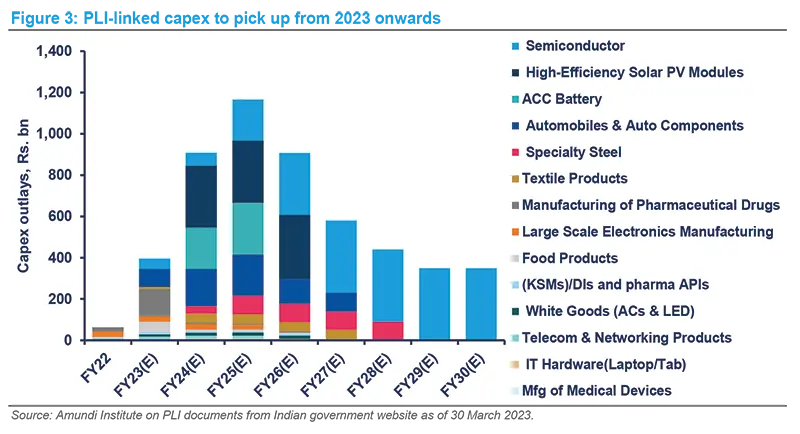

Boosting investment through Production-Linked Incentives

The Indian government introduced the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme for the first time in March 2020 within the mobile electronics space. The PLI’s success led the government to extend the scheme to other manufacturing segments and 12 more sectors were added in November 2020, followed by semiconductors (taking the total count to 14 sectors). Over the course of 2021 and 2022, the government consulted with industry experts and stakeholders to devise policy guidelines, while companies submitted bids. A final list of companies was drawn up based on their suitability and in FY22 and FY23 investments started in some sectors. According to the January 2023 Economic Survey of India, USD 6bn of investments were made leading up to FY22. The total amount of investments envisaged under the PLI over the next ten years is around USD 65bn or 18% of the annual corporate capital expenditure. Most of these investments are planned for 2023-2025 and entail subsidies of around USD 33bn (1% of GDP for FY23) spread over the coming years.

The final objective is to boost manufacturing by wrestling some supply chains away from China (such as mobile electronics, telecom equipment, solar modules and active pharma ingredients) and propel exports (like synthetic textiles). Among other things, the scheme aims to bring ‘sunrise’ industries like semiconductors and renewable energy to India. In the context of the transition towards greener energy and industries, Indian policymakers have provided a significant impetus for investments in electric vehicles, solar panels and Advanced Chemistry Cells (ACC) batteries, for example.

The PLI marks a significant departure from the past. Unlike previous schemes, it doesn’t favour all companies in each sector but provides select companies with an incentive to boost manufacturing activities. The government has also evaluated the possibility of building entire value chains domestically in a few targeted sectors such as solar modules, ACC batteries and semiconductors.

We do not believe that all of the initiatives will work. They are subject to trial and error, and there will be roadblocks along the way. For example, China’s recent export ban on the technology used to make solar wafers hinders India’s ability to augment its solar modules’ manufacturing capacity. Nevertheless, even at half the success rate, these initiatives would create significant investment opportunities.

The benefits of ‘China+1’ and a revised tax regime

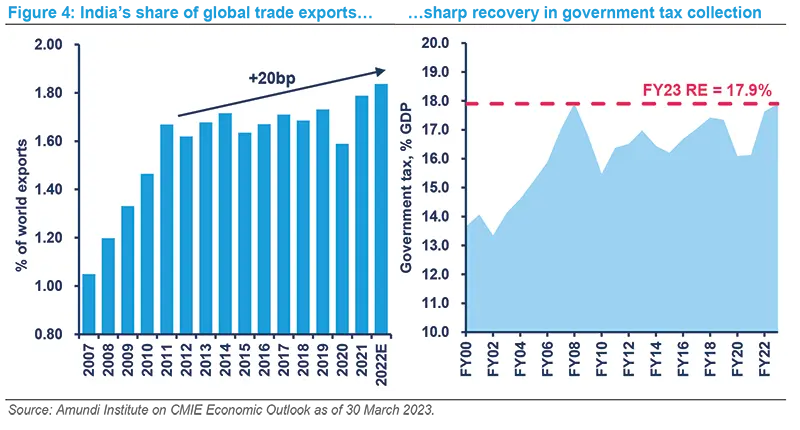

The China ‘plus-one’ strategy (China +1)1 has started working for India and has the potential to benefit its sectors. India’s share of world exports has risen 20 basis points, from a stagnating 1.6% during the last decade to 1.85% in the last two years. Over the medium term, the chemicals, textiles, electronics, electrical, and transport equipment sectors will be able to expand manufacturing capacity and boost exports.

The green energy mandate and the announcement of net zero 2070 have ushered in a series of investments in energy, including electric vehicles and green energy, beyond government PLI schemes. Moreover, various policy initiatives including the National Logistics Policy (NLP) and National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP) have increased the flow of orders for industries and businesses that are focused on infrastructure. The funding capacity of such an ambitious infrastructure pipeline is one of the objections encountered. The government’s attitude has changed significantly since Covid-19, and it is now more concerned about the ability of its expenditure to multiply growth. Capital spending by the central government increased from 3.3% of GDP during FY11-FY16 to 4.2% during FY17-FY23, with a further increase up to 4.6% expected by FY24.

The significant increase in government tax revenues as a percentage of GDP to a record high of 18% is another positive development. This is in spite of a 10% reduction in the statutory corporate tax rate in 2019 (a 7% reduction in the effective tax rate), as well as a 3% decline in the weighted average tax rate on indirect taxes since the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 20172. A significant overhaul of government operations has been made possible. In order to help the tax authorities close loopholes in the Indian taxation system and ensure better compliance, the Indian government has integrated the database for multiple direct and indirect tax collections over the years. The introduction of FASTag (i.e. electronic toll collection) resulted in a six-fold increase in toll collection in the last three years, helping to monetise roads. Additionally, unique biometric identities and bank accounts have helped the government to better target the benefits of a wide range of welfare measures.

The government's attitude has changed significantly since Covid-19, and it is now more concerned with the ability of its expenditure to multiply growth.

Over the next couple of years, India’s tax-to-GDP ratio could rise by 1-2%, which, if channelled to public and private partnerships, could spur infrastructure investments, net of political changes, regulatory bottlenecks, and policy risks.

Overall we believe India’s growth performance will continue to stand out among EM in the next ten years thanks to several factors, including: strong balance sheets, a protracted period of low investments, policy emphasis on infrastructure and manufacturing, the benefits of a China-plus-one strategy, as well as India’s own advancements in digitisation and fintech.

Looking out for the main long-term risks

Even though we think India is well-positioned for the next ten years, there are a few risks to be aware of:

- Commodities: Given India is a net energy importer, commodities are one of the country's main pressure points. Through their impact on fiscal policy, inflation dynamics and the external account, higher commodity prices will challenge macroeconomic stability. India's dependence on imported energy may be reduced by expanding domestic renewable energy capacity, but until then, India is susceptible to changes in the global commodity cycle;

- Political and policy risks: Despite the growing demand for greater welfare measures following Covid-19, the Indian central government has refrained from populist practices over the last few years. Instead, it remained focused on providing the essentials (such as medical supplies, free vaccinations and food grains, subventions and guarantees for specific loans). The same cannot be said at the State level, where giveaways are rising (India has a federal structure, with a Union government at the centre of several State governments). A concerted effort has been made to limit States' ability to borrow money for spending (the Indian Fiscal Responsibility Budget Management caps state deficits at 3% of GDP). This was partly made possible by the current ruling party (the BJP) having a strong political mandate, but challenges to its popularity may test some of these presumptions;

- Employment: In order for India to truly realise its demographic dividend and maintain social stability, the development of skills and the generation of new employment will be essential;

- Global risk: As stated before, India cannot be cut off from the rest of the world. India's future economic prospects will be significantly shaped by the development of world politics and economic growth.

- Transition risk: India’s uncoordinated target of achieving net zero emissions by 2070 may lead to more drastic and growth-disruptive measures, as delaying significant emissions reductions will increase the likelihood of adverse climate events.

India’s geopolitical role: strong cards to play, despite domestic woes

This was supposed to be a good year for India. The most populous country is preparing for a general election in 2024, presiding over the G20 and asserting itself on the international stage. India’s recent economic success has increased hopes in the West that the country may soon become a much-needed global growth engine and friendly geopolitical power in light of cooling relations with China.

However, the market turmoil associated with India’s recent biggest business success story, the Adani group, has cast a shadow over otherwise positive expectations for 2023. It has raised questions over the stability of domestic politics and how solid those positive expectations actually are.

Despite the above, political instability or a weakening of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s electoral prospects for 2024 are unlikely. Modi remains popular and scandals have failed to affect him in the past; the opposition is also weak.

It is also unlikely that these recent pressures will weaken India’s new-found power in the ‘great game’ of 21st century geopolitics. At a time when the Russia / Ukraine war and US / China tensions seem like a fight over prevailing world systems and beliefs, India could have the power to tilt the balance one way or the other.

India has benefitted from maintaining relationships with various powers throughout its history, despite Western pressure to condemn Russia, and this is unlikely to change. India will maintain its stance of strategic geopolitical ‘non-alignment’.

Russia has been a long-term strategic ally for India, for example during times of heightened tensions with Pakistan, when the US sided with Islamabad. Russia has provided India with military supplies and serves as a geopolitical counterweight to China, which India sees as a competitor, a partner, and geopolitical threat at the same time. Cheap oil from Russia also helps Modi achieve his goal of poverty alleviation and economic growth, increasing his electoral prospects. Furthermore, there is no appetite to add new adversaries to the list by alienating China and Pakistan.

India is also benefitting from the Western, and especially the US’s, resolve to disentangle itself from China. The US and India recently agreed on new tech and defence initiatives. These cover exactly the sectors the US has defined as sensitive in its relation with China and which will likely be slammed with new export controls on semiconductors, quantum computing, AI and 5G. In 2021, the US also entered into a new deal with India on solar panels, to weaken China’s grip over the market.

The EU is keen to advance a trade deal with India and Germany is making overtures to advance negotiations. Equally, the UK is keen to finalise a trade deal with India to show it can strike better agreements than the EU.

India’s status of geopolitical strategic non-alignment, and its recent economic successes, make it a potentially powerful broker between the East and the West, the North and the South. In sum, recent domestic woes are unlikely to weaken India’s strong cards in today’s geopolitical power plays.

Short-term outlook: boosting capex while pursuing fiscal consolidation

Growth: Beyond all expectations, growth performance has been strong since the full reopening in the second half of FY22. In fact, following a strong FY22 with a 10% YoY GDP increase, growth has settled at a still-strong 7.1% rate in FY23 and is expected to only decline mildly above its potential rate of growth in FY24 at around 5.6%. Domestic demand (consumption and private investments) has been driving the recovery, and urban India has unquestionably fared better than rural India. Private investments are gaining momentum as a result of the geopolitical changes favouring the country and the urgency to combat climate change. Due to a strong rise in imports (driven by domestic demand and a high imports bill) and a slowdown in exports (due to declining global demand), external demand has resulted in important trade deficits being a drag on growth; going forward, the large external deficit accumulated should narrow. Domestically, the rural economy should gain momentum in a pre-election year, although the announced FY24 budget was unexpectedly conservative in terms of expenditure / schemes favouring the rural economy. Rising tensions in the geopolitical arena, current domestic micro-reforms (if not the major macro-reforms), and extremely advanced digitalisation progress put India on the right foot to continue with a more than decent growth performance not only in the short term but even in the medium term. The public expenditure allocation towards capex is also expected to pick up speed (the infrastructure gap in the nation is still significant), supporting growth going forward, even though the Indian government is still pursuing a fairly prudent fiscal policy of consolidation.

Inflation: Indian headline inflation is erratic and challenging to predict, primarily due to the price formation mechanism in the food component which constitutes almost half of the basket weight. By the end of the last year, inflation had moved quicker than anticipated within the target range after peaking in September 2022 at 7.4% YoY, driven by favourable dynamics in vegetable prices. Unexpectedly, however, food prices in early 2023 caused headline inflation to move up once more and soar well above the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) target. India's food inflation remains at odds with the persistently declining trend in global food prices. It's unlikely the overall inflation figures will be less erratic until the price formation mechanism (i.e. middlemen, the monsoon season, a low productive rural sector, and top-down driven minimum support prices) stabilises. Despite a decline in inflation below 5% YoY in Q1 FY24, we expect inflation to fluctuate around the upper 6% band of the RBI’s target for the rest of the fiscal year. A more subdued demand outlook is resulting in a modest decline in core inflation, at 5.1% YoY in April 2023. Contrary to what occurred in 2011, when a significant fiscal stimulus and higher wages sharply pushed prices up, the current environment is conducive to lower inflation. The FY24 budget does not appear inflationary, and the RBI should be at the end of its tightening cycle, without pushing rates into growth-restrictive territory. However, the RBI will not be able to move more quickly towards monetary easing due to some stickiness in core Inflation.

Policy: The policy mix appears to be much more sound than in the past. In terms of monetary policy, the objective of achieving neutral real rates rather than restrictive ones aligned with the inflation and growth outlook has been clear since the beginning of the hiking cycle. In fact, the labour market is not tight, and the output gap is still marginally open. Considering the latest inflation figures and policy rate hikes, the RBI should already have reached its target. According to the announcement of the FY24 budget, the fiscal consolidation phase is still ongoing. The deficit target for FY24 is 5.9% of GDP, down 0.5% from the current FY23 target of 6.4%. Further reducing the deficit to 4.5% by FY26 implies a significant commitment beyond the next fiscal year. Regarding the budgetary items, the most encouraging development is the reaffirmed commitment to capital expenditures, especially in light of the significant multiplier effect that investments in infrastructure and productive capacity have on employment and growth: capital investments should reach 3.3% of GDP or nearly three times the amount in 2019–20. However, there is the risk of having capex adjusted in the event of fiscal slippage (i.e. lower growth dynamics or higher electoral expenditures). The FY24 budget is relatively less oriented to pre-electoral spending, reflecting the ruling party’s confidence in winning the upcoming national elections. Karnataka, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan will hold state elections in 2023 or early 2024 ahead of the national elections. Even though local factors frequently influence state elections, they should be closely watched to test the ruling party’s confidence and gauge voter preferences.

Opportunities for investors

Fixed income: resilient beyond short-term challenges

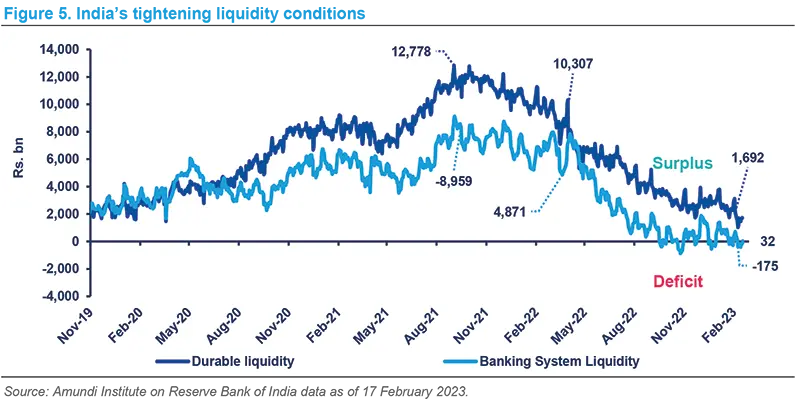

The outlook for Indian fixed income has changed significantly. This, however, does not signal a sudden change in monetary policy or a reduction in policy rates in the near future. Contrary to the situation a year ago, when all indicators pointed to a shift in the stance towards aggressive tightening, Indian monetary policy has clearly reached a stage where subjective assessments are relevant. The case for evaluating the lag effects of earlier actions is strong given the recent material change in policy rates and, more importantly, liquidity dynamics. The effective tightening has been between 325-350bp even though policy rates have increased from 4% to 6.50% since May 2022. This is because the operating target has shifted from being below the reverse repo rate to being closer to the repo rate. When viewed in conjunction with projections for growth and inflation, this would call for a short pause. In the very near future, a conservative policy stance will be required due to the focus on the midpoint of the inflation target and potential spillover volatility from external developments.

Navigating challenges from external spillovers and persistent inflation implies changes in policy rates, currency markets, and liquidity dynamics. While policy rate revisions have largely been completed, and given the recent changes in currency, further adjustments in liquidity will be essential. This might involve an extended period of higher market rates. Moving forward, cumulative adjustments in liquidity and policy rates are expected to impact real sector variables. More than 30% of bank lending is linked to external benchmarks, so much so that rate hikes are having an earlier and quicker effect on the real economy. The following support an optimistic medium-term outlook for domestic fixed income:

- The emerging growth-inflation outlook, along with the cumulative effects of earlier rate actions and a real neutral rate range of about 1% in the future, should allow for a pause in policy rate actions at about 6.5%;

- Market yields offer positive real rates for the majority of tenors on both realised and anticipated forward inflation measures;

- Fixed income yields remain attractive both on a relative and absolute basis, despite near-term volatility;

- Despite difficulties brought on by the higher stock of public debt-to-GDP, the outlook for fiscal consolidation is positive as tax buoyancy is increasing, driven by better compliance;

- Interest rate-sensitive flows within the capital account are far lower, even as the outstanding stock held by debt Foreign Portfolio Investments (FPI) is marginal. This is an essential factor that contributes to the external sector account’s high resilience to external pressures.

While challenges may persist in the near term, these factors should provide a high degree of resilience. There is potential for real positive returns from fixed income in the coming year thanks to higher carry and a lower estimate of future inflation. Markets may start factoring in expectations of a turn in the interest rate cycle, as the policy stance approaches a neutral zone and the growth-inflation mix becomes more favourable. Although the macroeconomic dynamics appear favourable for fixed income – including growth and inflation dynamics and the lagged effects of previous monetary tightening – markets may continue to face bouts of volatility.

There is potential for real positive returns from fixed income in the coming year thanks to higher carry and a lower estimate of future inflation.

Challenges and risk factors

- The RBI's midpoint target of 4%, combined with elevated core inflation of around 6%, would support maintaining a cautious monetary policy for a little while longer. After reaching the peak of its hiking cycle, the RBI should remain on hold over the coming quarters;

- As global markets adjust to the reality of ‘higher-for-longer’ policy rates for most developed market central banks, spillover volatility from external events may persist in the near term;

- The near-term visibility of capital flows is still limited and FY24's balance of payments is anticipated to remain negative. On the other hand, persistently tight liquidity may create opportunities for RBI open market operations (OMO) in the second part of FY24, especially given that data at that point may still be more favourable from an inflation perspective. The external sector balance sheet is adequately supported by a resilient surplus in the services sector, as well as stronger remittances and net foreign direct investment (FDI).

- The FY24 gross market borrowing of Rs 15.4tn remains challenging considering the strong credit growth in the banking sector. While that number was better than market estimates, how it will be absorbed in a situation of tighter liquidity remains to be seen.

Three routes for investing in the Indian bond market

The topic of India’s inclusion in various global bond indices has frequently gathered attention, most recently in the fourth quarter of CY22, but has always resulted in a continuation of the status quo. There has not been much progress in resolving stumbling blocks such as taxation-related concerns and Euroclear settlements. At the same time, the FY24 Union budget restored the withholding tax payable on onshore bonds to the statutory rate of 20% rather than the concessional rate of 5% that had been in place since 2014. However, non-resident investors pay withholding taxes at the rates outlined in their respective jurisdictions, which on average are likely around 10%. Elimination of the reduced withholding tax rate effectively prevents the government from providing any short-term tax concessions. This leads us to believe that the most likely way to facilitate index inclusion is through procedural changes to the FPI regime as a whole.

It must be emphasised that the FPI investment regime in Indian onshore bonds has recently undergone a significant liberalisation, departing from the quota-based, competitive access regime that was predominant a decade ago. Today, the Medium-Term Framework (MTF, for bonds and government securities), the Voluntary Retention Route (VRR, for all debt instruments), and the Fully Accessible Route (FAR, for specified government securities) govern FPI channels in Indian bonds.

1. FAR

The regime was introduced in April 2001. This option allows FPIs unlimited access to government securities defined by the RBI. Aside from any other tenors specified by the RBI, all new issuances of 5, 10 and 30-year government securities starting from FY21 are automatically included in FAR. The FAR currently includes 26 ISINs totalling USD 335bn in outstanding debt. Outstanding investments by FPIs are still marginal, at around USD 8.5bn. This is a large universe that is being considered by most index providers for potential inclusion. The FAR universe is completely open to FPIs and accounts for about 30% of the outstanding stock of government securities, which totals USD 1.10tn. By contrast, estimates of potential index-inclusion-related flows are mostly in the range of USD 30bn or a 10% weight of the index. This leads us to believe that the authorities’ apparent focus on ongoing procedural improvements may be a better way to encourage FPI investments. The FAR route is still the best route for gaining exposure to Indian government securities.

2. MTF

Investments in government securities, SDLs (state government securities) and corporate bonds are permitted under the MTF route, but only with certain restrictions on minimum maturities and an annually reviewed cumulative investment cap based on the total outstanding stock. A macroprudential short-term limit, which states that not more than 30% of investments in government securities and corporate bonds can have a residual maturity of less than one year, applies to FPI investments in government and corporate debt under the MTF. This route has limitations on the total holdings that FPIs may have at the ISIN level. However, there are no sales limitations and no lock-ins. The cumulative limit under the MTF for government securities and SDLs for this fiscal year is USD 61bn, of which only USD 9.25bn (15%) has been invested. Similarly, the limit for corporate bonds is USD 80bn, with only USD 13.1bn (16%) currently invested.

3. VRR

If FPIs commit to keeping a necessary minimum percentage of their investments in India for a period of time, investments made through this route will be exempt from the macro-prudential and other regulatory norms applicable to FPI investments in debt markets. At the moment, a minimum of 75% of the allocated sum must be kept for a minimum of three years. Any minimum residual maturity requirement, concentration limit, or single / group investor limits that apply to corporate bonds are not applicable to investments made through the VRR. This approach is therefore preferred for corporate bond investments, including parent-subsidiary flows and structured trades. The total investment cap under VRR is currently USD 30bn, of which USD 22bn (75%) has been allocated.

India’s green bonds initiative is on the rise

In 2015, a private bank in India issued the country's first green masala bond3, which was used to finance renewable and clean energy projects. The market for green bonds has gradually grown to include a number of public sector organisations, state-owned commercial banks and financial institutions, corporates and the banking sector. Green bond financing is picking up in India, with USD 7.45bn issued to date. According to Bloomberg data, these securities experienced steady growth of new issuance from USD 905.6mn in 2019 to USD 2.56bn in 2021, but issuances fell in 2022 to USD 978mn4. With a total issuance of USD 122 bn (according to CBI data) in green bonds, 2021 was one of the strongest years for EMs. India was the second-largest issuer of green bonds among emerging economies, behind China.

The framework for the issuance of sovereign green bonds (SGrBs) was announced by the Indian government in November 2022. It draws from the International Capital Market Association's (ICMA) Green Bond Principles providing best practice guidance on how proceeds should be used, managed and reported, as well as how projects should be evaluated and chosen. It offers a lengthy list of potential project categories that could benefit from the issuance of green bonds, based on these principles.

A Green Finance Working Committee has been established by the Ministry of Finance to streamline the project evaluation and selection process. An annual report on the allocation of proceeds to the eligible projects, the description of the projects financed, the state of implementation and unallocated proceeds are published under the Committee's supervision. Funds raised through green bond issuances are deposited with and made available through the Consolidated Fund of India (CFI). The Public Debt Management Cell (PDMC) tracks proceeds and monitors the allocation of funds to eligible green spending.

In January 2023, the RBI sold its first batch of USD 965.7mn in sovereign green bonds, with maturities in 2028 and 2033 and having cut-off yields of 7.10% and 7.29% respectively; a few basis points lower than those of government securities of equal length. In the current financial year, the RBI will hold an auction for approximately USD 2bn in sovereign green bonds. In February 2023, the auction's second tranche took place. The money raised from the SGrBs will be used to fund eco-friendly initiatives, such as pollution prevention, energy efficiency, climate change adaptation, sustainable water and waste management, and green buildings. Investments in solar, wind, biomass and hydropower energy projects will also be made.

Green bonds have become an important financial tool to address the threats and challenges posed by climate change over the past few years. India has pledged to reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 45% compared to 2005 levels by 2030 and to achieve about 50% of its cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil-based energy sources by that time. The issuance of green bonds will increase India's credibility in the global green finance ecosystem and encourage the country to stick to its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) goals. Transparent disclosure standards, reporting frameworks, and specific green project screening criteria will attract investors to India's sovereign green bond market.

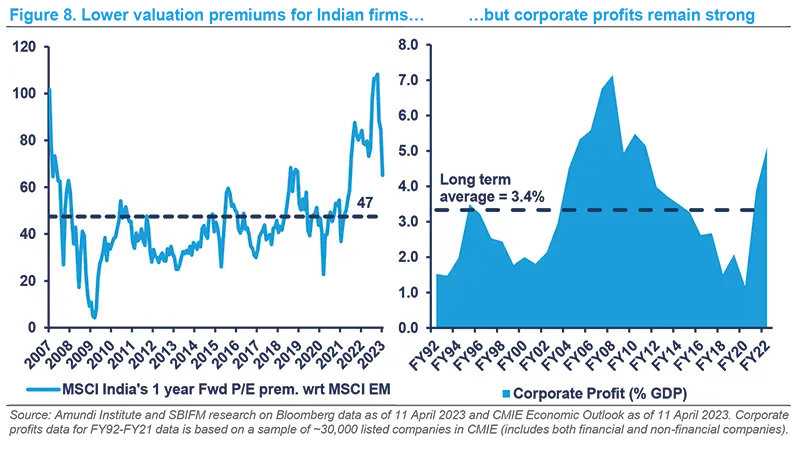

Equities: paving the way for a more durable recovery

Over the past two years, India has significantly outperformed global equity markets and its performance versus benchmarks for emerging markets has been even more pronounced. India's valuation premium relative to EMs increased to record levels as a result. The valuation premium, however, has started to normalise as a result of recent underperformance and now seems to be rapidly declining back to historical averages.

However, India's long-term growth story continues to be appealing beyond the short-term valuation excess. A number of factors have combined to support investment activity and India's profit cycle, including improved bank balance sheets, sound corporate balance sheets, leaner cost structures, reforms regarding corporate taxes and Production-Linked Incentives to name a few. A decade of low corporate capex activity in India, the emergence of new industries and China+1 all support the idea that India will likely continue to have a strong medium-term corporate capex cycle. After a ten-year hiatus, India is also on the verge of a real estate construction revival. Importantly, there has been a significant increase in the ratio of corporate profits to GDP following the secular decline between FY08 and FY20.

Correspondingly, there has been a noticeable shift in market dynamics, with cyclical industries, value stocks, and mid- and small-capitalisation companies doing well in the post-Covid recovery. This demonstrates how investor preferences are shifting away from low-yield companies and towards segments that are connected economically. Despite the fact that global headwinds may cause India's economic growth to slow down in FY24, we anticipate more balanced growth. Since high inflation reduced real incomes, mass consumption has lagged in the recovery thus far. As inflation cools, we expect this part of the economy to recover, despite potential challenges for sectors that rely heavily on exports. We, therefore, view 2023 as a year of adjustment, during which growth somewhat slows but also balances out, paving the way for a more durable recovery. India appears ready for a multi-year uptrend in economic growth and earnings, driven by a revival in manufacturing and investment, beyond the immediate adjustments.

Currencies: cautious optimism for the rupee

Along with other emerging market currencies, the Indian rupee (INR) has improved since the beginning of the year, with recent US dollar (USD) weakness sitting at the heart of this appreciation. Since mid-2021, the USD has been incredibly strong, pushing down the Chinese renminbi to its 2008 level, the euro and the yen to levels last seen in 2002 and 1998 respectively, and the British pound to all-time lows. Its rally ended in September 2022 and the dollar index lost 11% in the span of four months, although it marginally retraced in February 2023. The break in the dollar's strength was caused by the maturing rate-hike cycle in the US, mild optimism regarding the outlook for global growth in 2023 and a significant overvaluation of the trade-weighted USD.

It's true that the Federal Reserve’s rate trajectory still carries a degree of uncertainty. Despite the rise in advocates of a ‘soft’ or 'no landing', following the release of economic data in January, the US economy is slowing, concerns about the debt ceiling are growing and a sharper-than-expected decline in global growth cannot be ruled out. Geopolitical developments will also continue to weigh on currencies. These are just a few examples that could reverse the dollar's downward trend. The pace of Chinese growth in 2023 will also significantly impact the outlook for commodities. Despite these uncertainties, we are inclined to believe that 2023 might be a better year for the rupee than 2022. While the very near term may be a little turbulent, and we do not completely rule out some pain, we believe the currency may be better positioned 12 months from now.

In 2022 the rupee depreciated 10%, following a very mild 1.8% CAGR depreciation in the five years before. However, given India's deficit situation and high reliance on imported energy, the degree of depreciation was not excessive compared to other EM peers. The RBI lost 17% of its foreign exchange reserves between October 2021 and October 2022 as a result of its FX market interventions to control erratic movements. In recent months, it was able to recover part of its reserves. Regardless of its weakness against the dollar, the rupee was stable on an inflation-adjusted trade-weighted basis last year.

Between October 2022 and February 2023, other EM currencies fared better than the rupee, given its low correlation to mainland China’s reopening and the JPY’s recovery, driving a 5% correction in India’s real effective exchange rate (REER). Portfolio outflows are not expected to continue and we believe that the USD-INR will take part in the anticipated broad USD correction in 2023. Through a smaller current account deficit, reduced inflation, relatively better domestic growth and a maturing interest rate cycle, lower oil prices can also be a significant positive for the INR. Export growth has slowed rapidly, but India's robust manufacturing sector has kept the country's import bill high. But eventually, as global demand declines, India's imports of goods will likely follow. If oil prices stay around their current levels of USD 85/bbl, India's current account deficit could remain below 2% of GDP; every USD 10/bbl decline in crude oil prices reduces the annual current account deficit by USD 16bn. We anticipate a monthly run-rate reduction in the trade deficit of $4 billion in 2023, which will reduce the current account deficit by 1.4% of GDP.

Disinflation, meanwhile, might boost domestic demand and raise real interest rates, attracting bond investors and boosting confidence domestically. For the majority of the previous three years, the real policy rate was negative and only turned positive last December. Since November, both the RBI’s spot and forward foreign exchange reserves have increased. In conclusion, the rupee's depreciation rate may decrease significantly in 2023. While there are still risks in the near term, the INR may see a slight increase due to a maturing interest rate cycle, falling inflation, an improvement in the external account and relatively better domestic growth. The RBI's active intervention over the past eight years has also reduced rupee volatility and hedging costs.

Sources

1 ‘China plus one’ is the term ascribed to businesses avoiding investing solely in China and diversifying their business into other countries.

2 As per an RBI study, the weighted average tax rate under the Goods and Services Tax (GST) has come down to 11.6%, from 14.4% at the time of its launch. The revenue-neutral rate under the GST should be about 15.5% as per the Subramanian Committee report submitted before the GST launch.

3 Masala bonds are bonds issued outside India but denominated in Indian rupees, rather than the local currency.

4 SBIMF’s own analysis based on Bloomberg data for Indian green bonds as of 22 February 2023.

With the contribution of Giulio Lombardo, Digital Communication and Strategy Specialist,

Amundi Institute